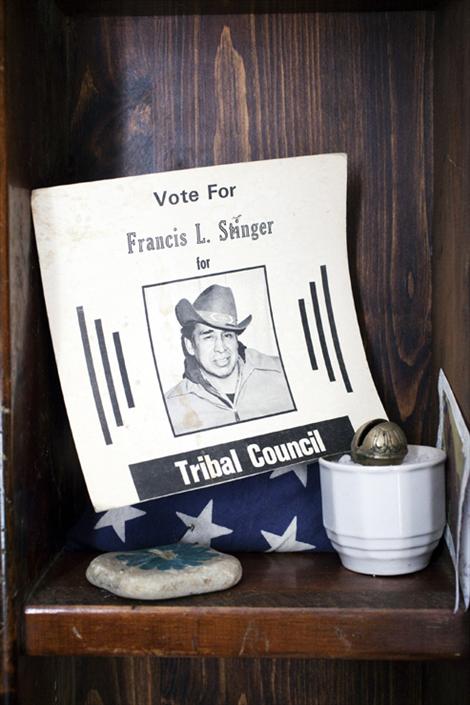

Local tribal elder recalls life milestones

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

It’s a typical family portrait; the child in the photo looks like he’d rather be eating spinach than getting his photo taken.

Francis Stanger was about 11 when the photo was taken with his “grandpa” Bill Finley — who was really a great uncle — Marcelline Finley Ashley, Bill’s sister; and their mother, Louise Lumpry Finley.

Now 85, Francis was born on Dec. 19, 1927.

He’s Salish, Pend d’Oreille and Colville. Stanger is a Colville name, and his grandfather’s name was Willie Stanger.

After Francis’ birth, his mother, Agnes Felix Sabine, contracted pneumonia and died.

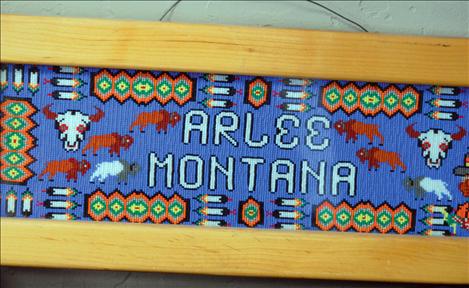

Francis grew up in Turtle Lake.

“Three old bachelors raised me,” Francis said. They were his dad, Frank Stanger; Bill Finley; and Louis Finley, who lived to be 100 years old. His grandmother, Louise Lumpry Finley, went blind when she was 99 and lived with the group until she died at 112.

“She came on the trail of tears from the Bitterroot,” Francis said.

With the exception of his grandmother, they were all bronc riders, so Francis wanted to be a bronc rider, too.

But they told him, ”No. You’ll get all busted up.”

His dad used to ride a horse to town and tie him up. High school girls who knew him would come down, untie his horse and ride around town. When Frank wanted to go home, he had to go all around looking for his horse.

Finally he rode a green-broke bronc into town, and the girls couldn’t ride the feisty horse.

“He educated those girls,” Francis remembered, smiling.

“I grew up in the horse and buggy days,” Francis said, recalling a trip to Browning Indian Days in a wagon when he was 3 years old.

At home, they had kerosene lamps and no telephone, no TV, “no nothing,” Francis said, but he believes people were happier in those days.

Today, he noted, even the wealthy aren’t happy.

“Sports people got all that money — millions — and are crying around for more money. Greedy,” he said.

His family would all come to town about once a month for groceries and such. Francis remembers different businesses in Polson — Davis Mercantile, Voss’ Meat Market, Funke and Sons Clothing Store and the Red and White Grocery.

“I went through the Depression; we had to hunt and fish to live,” he said. “First deer I shot when I was about 11, with a .22 single shot.”

He listened to his grandfather tell “coyote stories, stories about everything.”

Both his dad and granddad played the fiddle, and his dad also played the drum.

Plus “Indian people got a sense of humor,” Francis kept saying.

He attended Polson schools until the 8th grade when he transferred to the Chemawa Indian School, 50 miles north of Salem, Oregon. It was a part-time industrial and part-time academic school. The school was self-supporting, according to Francis, with apple trees, a bakery and a barbershop.

A Salish speaker, “I was a top student at Chemawa,” Francis said, adding that he was a pretty good artist.

Francis took up farming and worked in the dairies, getting up at 4 or 5 a.m. to milk cows and then milking again in the afternoon. He spent a year at the school.

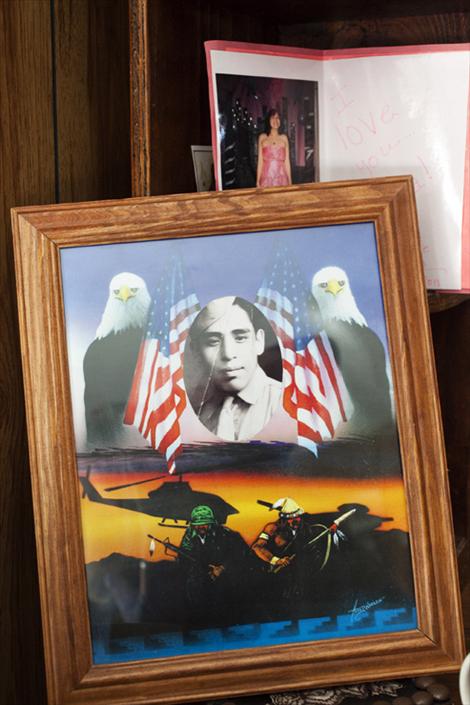

After school, Francis joined the United States Marine Corps when he was 17. He served in occupied Japan and in the 1st Marine Division in China. He was a military policeman in China, but also worked as a cook, a machine gunner and a guard.

As well as having several love affairs, Francis married three times. He married Teresa Lozeau when he was very young. Later he married Martina Quequesuh, and the couple had three children — Mike, Amelia and Frank. Martina passed away in 1986. Later, he married Tiny Robbins, a lady from Butte. Right now, he’s single.

“I had a lot of sweethearts in between,” he said, smiling.

So far during his life, Francis has ranched; worked as a sawmill hand at the Dupuis Mill running the green chain, forklift and carrier chain; and worked for local farmers. Francis retired from Mission Valley Power in 1993 after working there 10 years.

When asked to think about the good times, Francis said, “When I sobered up. I was a professional drunk.”

His son Frank was born in 1971.

“He was a year old when I quit drinking. I haven’t had a drink in 43 years. I’ve become a prayer leader,” Francis said.

He’s also a member of the Sober Indian Riders and proud of his years of sobriety.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars helped him, especially after the family had a fire.

“I didn’t join them, they joined me,” he said.

Now he’s very dedicated and involved with the organization.

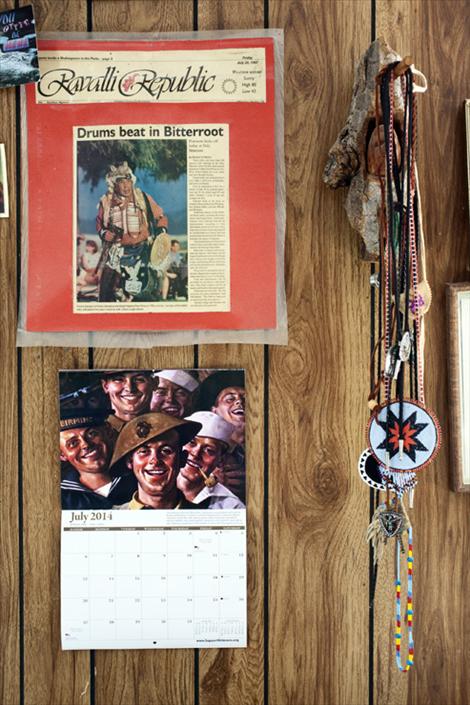

He’s also always been involved with powwows. Francis said he put on a lot of them, too. Traditionally, first they pray at a powwow, then bring in the American, Tribal and Canadian flags. The prayer leader says a prayer, and the drum plays an honor song for the flags and then they play retreat and the dancing begins.

All his dance regalia was either given to him or he made it.

“I dance the old style,” he explained.

Powwows nowadays are more commercialized, he said, and the drums are losing the beat.

“The golden agers, they don’t give them a chance to dance,” he explained

It used to be, Francis said, grass dancers came from the east and had regular grass on their outfits. A dancer would go seven steps one way and seven steps the other, and pray for the grass.

Fancy dances started in 1945, he said, in Oklahoma. Jingle dresses came from Wisconsin from a dream, Francis said, with one “bell” or jingle for each day of the year. Chicken dances came from the Salish, watching prairie chickens.

“A war dance — how you fought the enemy. Every dancer should tell his own story,” Francis explained.

Francis traveled to Japan in a dance troupe.

“It was an Oriental festival, gathering dancers from different cultures,” Francis said.

The festival lasted four days, and the Japanese loved the parade and the Indian dance outfits. The Salish followed the Blackfeet, and “the Blackfeet never go without music” so they played drums.

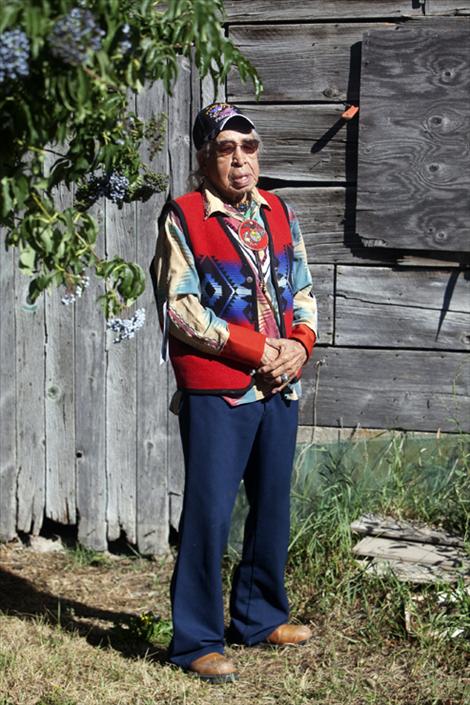

Francis Stanger – elder, dancer, prayer leader, father, grandfather, comedian.

He wears lots of hats, even a headdress or a coyote cape, and continues his busy life.