Officials debate finer details of compact ahead of deadline

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

Plans for shared water shortage in times of drought, irrigation canal improvements, and delivery of funds were debated by state, tribal, and federal officials Friday in a negotiating session for the proposed Confederated Salish and Kootenai Water Compact.

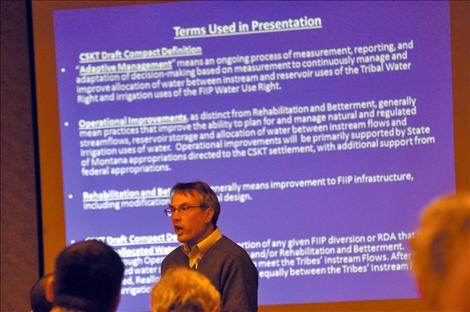

Most of the elements of discussion were a part of an adaptive management plan that was born in the summer months to address irrigator concerns about modeling data used to draw up water allotments for irrigation turnouts on the Flathead Indian Irrigation Project. The state’s legislative Water Policy Interim Committee set up a technical working group that in September found the modeling data to be sufficiently sound for the compact to move forward as it was. However, state and tribal officials offered up a flexible plan of adaptive management that will provide contingency measures to help get extra water to irrigators if reality does not bear out what the models have predicted.

“Adaptive management is really an interactive and ongoing circular process of measuring water, measuring the quality of irrigation water management, in-stream flow management, and reporting on that, and trying to change and adapt and improve your farm,” Tribal Hydrologist Seth Makepeace said. “It is just trying to increase efficiency and improvement in water management and implementation of water rights settlement.”

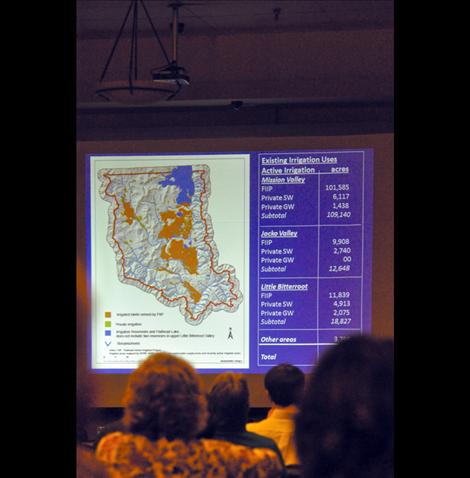

The adaptive management plan calls for a team of tribal and state members to form a board to analyze and alter, as needed, strategies for delivering and saving water on the Flathead Reservation. It also provides for an unspecified amount of funds from the federal government to be used to rehabilitate the deteriorating irrigation project to boost efficiency. Money would be put into transitioning the project from the open-air canals that currently leak as much as 50 cubic feet per second into a system of more than 60 miles of underground pipe that would not leak as much.

In a five-year deferral period monies will also be used to implement measuring of water on the project that has previously not been done. After the deferral period, the enforcement portion of the compact will kick in.

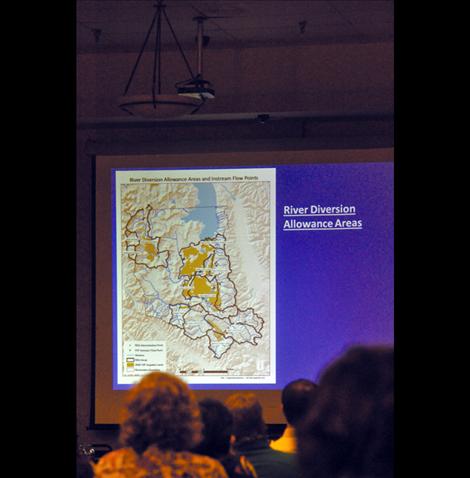

During that phase, dry-year minimum enforceable flows will be met as will river diversion allowances that bring water to the head gates on the irrigation project.

Once those two water allocations are met in wetter years, water will then be assigned to meet target in-stream flows. Waters saved by efficiency improvements on the project will then be split between in-stream flows and the irrigation project, Makepeace said.

In years of drought, both the Tribes and irrigators will endure lesser allocations of water. The minor drought, the Tribes would only receive minimum enforceable flows, while river diversion allowances continued to be met. If the drought grew to be equivalent to some of the worst on record, the senior tribal water right would kick in and the minimum in-stream flows would have priority, while river diversion allowances would be met where possible.

In dry years, the Tribes will be make available mitigation water for lease to give farmers an option to deal with drought.

State officials want to make sure that water is accessible to irrigators in drought years.

“Our contention is that in order to protect existing uses, that water can’t be provided in theory only,” Tweeten said. “It has to be available as a practical matter and that means it has to be priced at a level that the irrigation project users can actually afford. The number that’s in the Compact — $40 per acre foot — is probably more than the irrigators will be able to afford, especially if they are in the second or third year of a long-term drought.”

Tweeten asked that the water be provided at a much lower cost for irrigators and that monies be devoted to subsidizing the pumping costs. Tribal authorities were lukewarm to the idea.

“What is a fair price?” Tribal Attorney Rhonda Swaney said. “I guess this is an issue we will have to take back to our client. We wouldn’t have that cost in the compact, but for the state’s requirement that we put it in there.”

As for subsidizing the pumping costs, Swaney pointed out the irrigators will receive many financial incentives in the compact that could be put toward pumping the water. She said the Tribes believe it is highly unlikely the drought conditions would ever be so extreme the extra costs for pumping would bear out in reality.

“We understand the fear is out there, but we feel that the $30 million pumping fund could be accessed for those kinds of extraordinary costs, and believe for the most part that they won’t ever come to pass,” Swaney said.

State officials also wanted to make sure federal funds that the Tribes have promised to earmark for betterment and improvement of the irrigation project are spent appropriately and in a timely manner before the enforcement period kicks in five years after Congress allocates funds for the settlement.

“There’s no provision in the Compact that we’re aware of that provides some redress in the event the money and allocations that have been earmarked for these purposes doesn’t get spent,” Tweeten said.

Swaney said she understands the state’s apprehension, but the Tribes also have their own concerns about Congressional funding.

“I understand the state’s concern, but I would like to wish to share the Tribes’ concern – that neither the state nor federal contributions will be appropriated timely,” Tribal attorney Rhonda Swaney said. “There begins an out of time on the deferral because the deferral doesn’t begin until it is appropriated. That burden lies directly on the Tribe. The fact that the irrigators continue business as usual for that period until funds are appropriated, and through the deferral period, doesn’t put any burden on them. I disagree with your statement that the burden lies just on the irrigators. I think the burden lies directly on the Tribes and we’ve never had problems spending money when it’s available. The problem is getting money.”

As the finer details are parsed out, Makepeace said the Tribes have compared the water allocations to actual historical data compiled by the Tribes over two decades. He said he believes that the compact will be able to meet the Tribes and irrigators’ needs even before the water-saving efficiencies are put into place.

“We didn’t model improvements for rehabilitation and betterment – canal lining, improving the pumping plant,” Makepeace said. “Those aren’t part of the allocation numbers. That enhances our confidence we will be able to meet these stream needs.”

The compact is in the final stages of renegotiation after it initially failed to pass the legislature in 2013. It would settle the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes’ federal reserved water rights claims. If the compact is not approved, tribal leadership have stated that they will file water claims that reach as far east as Bozeman. There is a June 30, 2015 for filing the claims.

The renegotiation of the compact resulted after the Flathead Joint Board of Control fell apart in early 2014 and was unable to sign the Water Use Agreement. The state is now negotiating on behalf of irrigators.

“I haven’t been authorized to say this, but I remain optimistic that we’re going to be able to rebuild the compact and put it into a condition where we can submit it to the legislature for consideration in the 2015 session,” Tweeten said.

The legislative session begins in January.