Polson veteran defied death in Vietnam

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

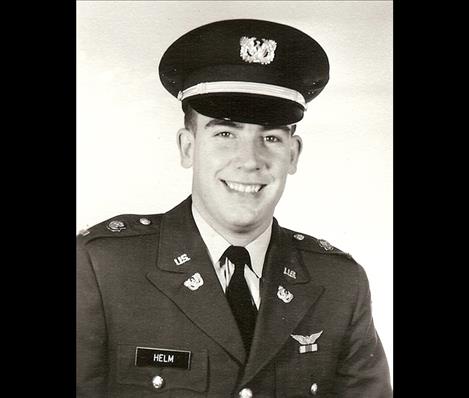

On Veterans Day, flags are raised during the federal holiday to celebrate the many sacrifices veterans make for this country. Retired U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer Pruett Helm is one of those veterans. For him, the holiday is also the exact day he ended up on the jungle floor in Vietnam paralyzed from the waist down.

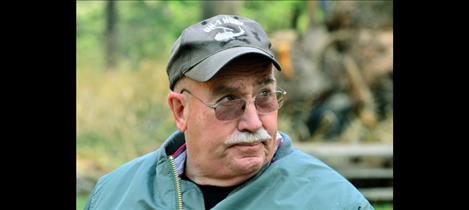

Helm recently settled into his wheelchair in his home surrounded by pine trees to tell his story. He moved to Polson 35 years ago. His wife, Sherrie Helm, sat across from him. They’ve been married for 43 years. Helm is now 72.

As he began to speak, the image of a helicopter spinning out of control in the jungle of Vietnam came to his mind. The helicopter went crashing through the trees, shredding vegetation, and he was in it. He was 22. It was Nov. 11, 1966.

The UH-1C Huey helicopter crew with D Troop 1/10 CAV was on a rescue mission with five other helicopters. Two more crashed and exploded instantly after taking on gunfire. Helm was the co-pilot that day. After the second pass over the jungle, the aircraft was shot down.

“From the moment we started taking on rounds, things started to go into warp speed,” he said. “The helicopter burst into flames in the rear. We could smell the smoke in the cockpit.”

Two door gunners were firing into the trees. The two pilots braced for impact. Helm was knocked unconscious. He thinks he was out for only a few seconds.

John Fish was the door gunner and he filled in the time Helm was unconscious in a report compiled by Colonel Phil Courts with other testimony called “Shootout on the Cambodian Border.” He said bullets were coming through the helicopter, and for him, time suddenly slowed down.

“Pieces of metal seemed to be floating in slow motion,” he added that dirt and leaves were everywhere and in his mouth. Helm, he said, was just sitting there, not moving. His legs were tangled around the pedals like a pretzel. The aircraft was now on the ground.

“I came to with John Fish yelling at me and pulling at me trying to get me out of the helicopter,” Helm said. “I was in a daze wondering why my legs weren’t responding.”

Fish pulled Helm from the helicopter and dragged him a few feet away. Two minutes later, it exploded. Helm lay on the jungle floor with a broken back. His comrades were also hurt and suffering from burns. Forty-nine-years later, Fish still had round scars on his feet where the metal shoelace eyelets burned into his skin.

After the explosion, the crew started to assess the situation. It was about 10 a.m. It was horribly hot and humid. Vietnamese were in the brush around them not too far away. The crew had a few weapons but little ammunition. They needed help. An American crew saw the explosion and reported that no one could have survived. Assuming the crew was dead, American air strikes were called into the area.

“When you are on the receiving end of American firepower, I’ll use the word terrifying,” Helm said.

He was in and out of consciousness all night. The sounds of exploding bombs were all around them. They listened to the clunk of shrapnel as it hit the tree trunks around them. Helm would still have pieces of shrapnel embedded in his body years later.

“Our main objective was to stay quiet,” he said.

They lay there until the next day, and they were feeling the symptoms of dehydration.

“We could taste smoke and dirt in our mouths,” he said. “We were so thirsty.”

They were eventually spotted by friendly aircraft. A CH-47 Chinook with two large twin rotor blades was sent in to rescue the crew. One-by-one they were pulled up in a large basket. But before it could take off, the aircraft started to draw fire.

“I felt so incredibly helpless and vulnerable dangling there on this cable,” Helm said of being pulled up into the aircraft that flew away just in time.

Helm was taken to a field hospital in Qui Nhon where it was discovered that his kidneys were shutting down. He was then moved to a hospital in Saigon a few days later.

“This is where the story gets unbelievable,” he said. “I choose to use the expression ‘blessed’ to explain it.”

It just so happened that an artificial dialysis machine was on a ship that had docked in the nearby Saigon harbor. And the machine was on the top level of the cargo ship. If it was on the bottom level, finding it would take too much time.

“Without it, I wouldn’t have made it,” he said.

In the meantime, a yellow cab arrived at this parent’s house to deliver a Western Union telegram that said their son was shot down and missing in action. Twenty-four hours later another telegram came that said he was missing in action and presumed dead. And finally, a third telegram arrived saying his body was extracted from the jungle and he wasn’t expected to survive.

“My parents didn’t know anything else for some time,” he said, adding that he wished they hadn’t gotten the telegrams.

On day 45 of his treatment, he thought he might eventually be released to join another crew.

“I still thought it was a bad dream, and I would wake up and go back to normal,” he said, but in reality, he had to find a new normal. Six months after the helicopter crash, Helm did find John Fish by accident.

“He assumed I was dead,” Helm said. “When we saw each other it was elation and tears of joy. We’ve been friends ever since.”

Helm would eventually be released from an American hospital, undergo rehabilitation, and he would walk with sheer arm strength and crutches for about a decade before needing a wheelchair full-time. He found a job as an air traffic controller, making him the first person in a wheelchair to be hired by the Federal Aviation Administration.

“If I couldn’t fly them, the next best thing was to be in proximity,” he said of aircraft.

He also got married, had two children, and learned to ski in a toboggan of sorts. He loved riding horses. On this Veteran’s Day, like all the others, he will celebrate again.

“Because of war, death and disability are inevitable,” he said. “You look death in the face and choose to be thankful for what you have.”