Drug courts offer addicts a path to get clean

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

Lauren Pope struggled with drug addiction for more than a decade.

In 2013, things were so bad that she thought getting arrested would be the only way to clean up, so she stole a bottle of Worcestershire sauce from a Rosauer’s in Missoula.

“I made sure that that security lady saw me put it into my purse, so I would get put in jail,” she said.

Pope was already on probation and she thought the theft could be enough to possibly send her to prison.

It was her shot to stop the spiral she’d been in since 1999.

“After divorcing a man who was an addict, I was here as a single mom – first time going to school – started hitting the party scene and someone introduced me to meth,” she said.

“When I smoked meth off tin foil, it just, it’s what had been missing my whole entire life. And then I wanted to do it every day. I literally lost everything in about six months. It took over, stopped going to school, stopped going to work. I started cooking meth within that 6 months. Beg, borrow, steal. Lie. Sleep in cars. Pawn my kids off on whoever would let them stay on their couch. It’s a very typical meth-induced life that I lived,” Pope recalled.

But instead of getting thrown in jail, Pope was introduced to something called treatment court.

It’s an alternative to lock-up offered as an option to some people with drug-related felony charges. Pope, who was able to get clean once before the relapse that led to her 2013 arrest, was accepted to the program. It meant she kept her independence. But she’d also have to prove she was keeping her act together. She had a social worker, an addictions counselor, a probation officer and a public attorney working on her case. And she had a set of tasks she had to do to stay out of jail, including regular urine tests.

“We have to find our own housing. We have to get a job. We have to continue to move forward. You know, moving backwards was not an option,” she said.

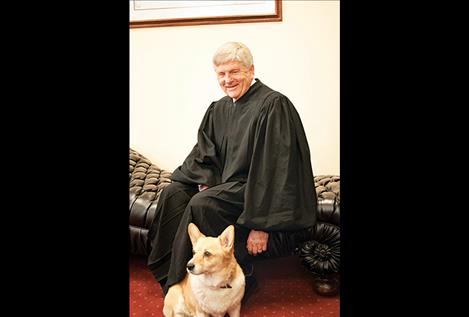

This opportunity for Lauren Pope came about because of one judge – John Larson. In 1996, Judge Larson started the first court of this kind in Montana. And it began in the juvenile justice system.

“I thought a more intense effort would be beneficial, just because you have such a short time with the kids, you better spend a lot of time with them if you’re going to make a difference,” he said.

Larson’s approach had never been tried in Montana. Instead of just processing drug offenders, the youth court worked to understand how kids got addicted and how that led them to the court. It required that the court listen and learn from these teenagers and invest in their success.

“There’s constant contact with them, and we know what’s happening in the home, the school, and any other place the youth happens to think he’s not being monitored,” he said.

Larson’s youth court became the model.

From 2004 to 2011, Missoula County set up similar courts for families, veterans and for co-occurring cases -– like Lauren Pope’s – which involve both mental health and substance abuse problems.

The model expanded elsewhere in the state. Montana now has 31 treatment courts, including adult and tribal courts. In the U.S., there are more than 3,000 drug courts. A lot of them look a lot like what Larson pioneered here.

Chris Deutsch works for the National Association of Drug Court Professionals, which has its headquarters outside Washington, D.C., and exists to help people like Larson. But Deutsch says Larson did his fair share of the lifting.

“One of the challenges Judge Larson certainly had was convincing the community at large that what we’re currently doing isn’t working, so we need to try something else and here’s a solution that offers a lot of promise,” he said.

The reason these kinds of courts replicate is because there’s some proof that they work.

“Drug courts really benefitted from a body of research that almost immediately started to be established. Researchers started to look at drug court, they needed to know does this work, does this reduce recidivism, does it reduce crime? And almost immediately that research showed positive outcomes and that only fed the desire for more programs,” Deutsch said.

In Montana, statewide stats on recidivism show that drug courts keep re-offending rates down.

According to a 2017 report from the Montana Supreme Court Administrator’s Office, 71 percent of adult drug court participants did not re-offend in the three years following their completion of the program. Data show graduates are more likely to get jobs and keep their families intact; they’re better equipped to lead productive, positive lives.

These courts save money. In Montana, for example, it costs taxpayers an average of $4,500 for each person who’s in treatment court. Contrast that with what it costs to keep someone in prison for a year – around $30,000.

Over the years, the treatment courts have evolved to deal with what drugs people are doing most often. In Montana, meth use has surged. Since 2013, it’s become – by far – the number one drug used by parents whose kids end up in Montana’s foster care system.

“Now, almost all of the treatment programs have to have some focus on meth, because these people are getting into it. I mean some are in opiates and some are in alcohol, but I think meth is sort of a common thread weaving them together,” Larson said.

He’s seen up close how meth impacts children and families.

“We have kids testing positive that are under a year and they’re just like these corgis in my chambers here, they’re little vacuum cleaners. These kids are sticking their hands in their mouths, they’re getting in the carpet, they’re on the table maybe, or some other place where the meth is, and they get it,” he said.

Meth is the primary drug of choice in nearly a quarter of all drug court cases. For juveniles, it’s rare, but still present.

At Larson’s youth court meetings, he and his team discuss the kids case by case, talking like a table of concerned parents. They want to know where these kids have been, who they’ve been with and what they’ve been up to. There’s disappointment, exhaustion, frustration. But the team doesn’t give up. If a kid starts slipping, the court may take away privileges, put them under house arrest, even lock them up for a while. In Larson’s mind, there’s never a break from what’s at stake.

“You just can’t stop and you just can’t ‘oh, they had a good week, so let’s give them a month off.’ You really have to keep attached and keep working, support their success because it’s too easy to go back,” he said.

For youth court, Larson and his team meet weekly. The people around the table include case managers, probation officers, public defenders and youth counselors, among others. The team is dealing with all the issues that affect teenagers – plus, drug use. They’re helping them get their first paying jobs. Keeping them from skipping class. Sometimes, they even weigh in on prom.

It’s a give and take process. When a teen is making good on goals established by the court, they move forward in the program. If they’re backsliding, the court takes measures to force change.

Lauren Pope was familiar with youth court and Judge Larson before she entered treatment court. She came to him first as a mom. Her daughter, Jodi, was in youth court when she was 13.

“I fought tooth and nail with that court. I made an ass of myself a lotta times in front of Judge Larson. Youth court watched me go from recovery to relapse to recovery again … and they got to see my daughter react because of it,” she said.

Jodi does not have fond memories of her time in Larson’s court.

“When I think of drug court I think of being locked up, steel doors slamming, I think of screaming kids, getting thrown in padded cells. Nothing positive. I think of being taken away from my mom,” she said.

Jodi’s drug use had started with pills and pot in her early teens. She spent three years in youth court the first time, graduating at 16, but the effects didn’t stick. She went back to partying and was in front of Larson again within a year. That time, she didn’t finish, aging out just before turning 18.

During her five years in the program, she says the court shuffled her around to different treatment and psychiatric facilities to keep her away from her mom, who was then using meth.

“They ruined my teens. I got one dirty UA (urine analysis) and I was in there for years. It’s was like I was being punished for my mom’s behavior,” she said.

Jodi admits she wasn’t prepared then to commit to treatment. Partly because of that, the court’s consequences and authority were hard to take. Every time she made some progress, she rebelled. She doesn’t think she was old enough to know any better.

“I guess the difference between me and my mom’s experience would be she was an adult so she could take that. I was a child, you can’t expect a child to have that responsibility,” Jodi said.

“In order for a parent-child relationship to be successful if you’re going to go through treatment court, you gotta have both participants being willing. My daughter wasn’t willing,” Pope said.

It’s complicated. Because families are. When Jodi was in treatment court – dealing with a parent addicted to meth – she still wanted her mom in her life and she felt like the court wanted to get between them.

But from the court’s perspective, it was trying to help a teen stay clean.

When they begin the program, participants must submit urine samples on a daily basis. That includes showing up on their own to Compliance Monitoring Systems, the private company the court contracts to run the testing.

“Everyday their internal convictions have to be stronger than their cravings, and so that’s what you work on with these individuals, and it is one day at a time,” Jodine Tarbert, of CMS, said.

Tarbert has worked in different aspects of the medical field – for orthopedic surgeons and at a chronic pain clinic. She’s seen a lot of drug abuse that starts with prescriptions and moves on to drugs like meth.

Her past paved the way for the alcohol and drug monitoring program she developed in 2008. There was nothing like it in Montana at the time.

“When I moved on to drug and alcohol monitoring I felt I had such a different insight…we weren’t to the point where we were treating the whole person, we were just trying to mask their pain. I knew there was so much more that was going on in their lives than just the abuse, then just the addiction. You need hope, you need to know that there is a solution for your problem. You can recover,” she said.

Around the corner from her office, Joe Sickels, the lab manager at Compliance Monitoring Systems, is working surrounded by humming machines.

“I pretty much oversee all the treatment court testing in Missoula County,” he said.

Sickels knows every single person’s drug test. He shows up to the treatment court to deliver results directly to the judge, sometimes just minutes after getting them. It can be a moment of reckoning for the participant.

“The whole point of drug testing isn’t like a ‘a-ha I caught you,’ a big part of it is knowing where they are in their recovery and … get them the result they need to see where they need to go further in their treatment,” he said.

The quicker the results come in, the faster issues are addressed in the court. The first few months can be tough. There’s usually a lot of denial. For a recovering addict, other drugs can creep into the picture, so the lab tests for a big spectrum of substances. Sickels gestures to a cluster of sample vials loaded into a tray.

Getting clean results doesn’t always tell the whole story. Sickels and Tarbert are trained to look for other signs that someone is using. But again, it’s not about shaming or condemning them.

“Anyone that comes to work for me here has to have that ability to see the glass half full and really understand that we’re here to help them through the process, I’m not here to judge anyone,” Tarbert said.

That’s really the whole point. This is a court backed by this huge cast of people not typically in the business of handing down judgments. Take Hannah Halden, who works as the coordinator for the co-occurring and veteran treatment courts in Missoula.

“Someone nicknamed treatment coordinators like a ‘multi-tasking ninja,’ because you just do everything. I’m kind of a social worker, case manager, and compliance officer all rolled into one,” she said.

Halden is usually the first contact with treatment court participants – and that is what they call them – participants, not criminals and not clients. She said that initial meeting can be a little awkward.

“I’m a total stranger. I’m asking them to tell me every single embarrassing and uncomfortable thing they’ve been charged with in the legal system,” she said.

Halden’s goal is to gain trust and establish herself as an advocate in these peoples’ recoveries.

One of the first things she does is connect people with healthcare and counseling services. Housing usually comes next—half of the people who enter the program are considered homeless. From there on out, Halden’s talking to participants through their day-to-day struggles. Helping them maintain focus on their goals.

Halden said 60 to 70 percent of the people she works with are using meth. With such a destructive drug, Halden said, it’s vital to invest in long-term addiction management through programs like treatment courts.

“In the department of corrections, it seems like many of the people with mental health issues that are there aren’t getting the kind of treatment that will help them stay clean afterwards,” she said.

“When we incarcerate them, that’s a punishment, but we don’t really do anything in that process to teach them different skills when they get out,” she said.

For Lauren Pope, that approach worked.

“I started as a street junkie, went through treatment court, graduated … finally and now I get to hear people going through treatment court,” she said.

Pope now works as a peer support coach for recovering addicts entering treatment. She says there’s something completely profound about one addict helping another.

“We have shared life experiences and I get to walk beside them and show them and help them and encourage them to reach out, love themselves, stay clean, get support, give them hope, give back,” she said.

Pope said she is the happiest she’s ever been. Her daughters, now 21 and 26, are a big part of her life.

“It’s funny, they’ve seen me clean and in recovery much longer now than in active addiction, but it’s the active addiction part that has stuck with them. That’s what they remember and that’s what they have to overcome is being raised by a mom on meth,” she said.

Her daughter, Jodi, just after leaving the treatment court system at 18, came into some familiar family demons.

“Meth … just like her momma,” Pope said.

Now, Jodi has been clean six months. She and Lauren are a lot closer and talk every day.

“Treatment court saved my ass. Honestly,” Pope said. “It gave me a second chance … to be a good mom.”

This story was produced as part of a series exploring the impact of methamphetamine use on Montana. More from the series can be found at metheffect.com.