Veteran Spotlight

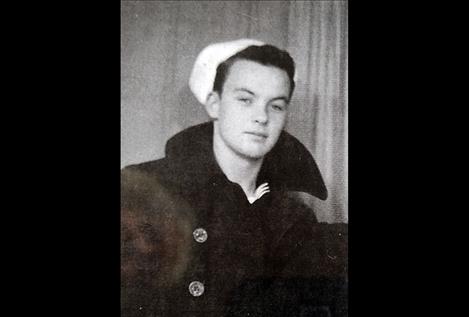

William A. Browning February 12, 1927 WWII: Seaman 1st Class U.S. Coast Guard

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

Who would have thought a young man in 1945 would travel virtually around the world at age 18? Not Bill Browning, who was then in high school. Bill has a newspaper picture of himself helping with the “Buy a B-29 Bomber” Sixth War Loan Drive at Lincoln High School in Seattle, Washington.

At that time, the armed forces were low on people so Bill’s choices were to finish high school under the draft and then go wherever they wanted him to go, or to leave high school and join what he wanted to be in. Bill always liked the water, and in seventh grade actually built a boat. He decided to join the Coast Guard and left school early. Bill did finish school and graduate while in the service by sending his lessons back to Lincoln High School.

January 1945 found Bill in boot camp at Government Island, Alameda, California. Bill says boot camp is for learning ordinary stuff: Lesson 1. Discipline, Lesson 2. Discipline! He also learned to respect the military and think in terms of working together. He only spent eight weeks there, but it was 24 hours a day. He finished in good health and four days later was on the Coast Guard troop transport A. W. Brewster out of San Francisco, California. Bill was excited and got seasick this first time on the ship, but not after that.

Orders were very secretive because they were responsible for lots of lives, so not until they were underway did they get their orders to go by way of the Panama Canal to England. In Bristol, England, Bill got a chance to leave the ship on a 4-hour pass, but he had to go in a group of not less than four. He and his buddies walked about two blocks and came to a park. The city had been bombed and the park was a mess. Three or four English girls came up and sat and talked to them. The girls, cool as cucumbers, pointed to where their homes had been blown up. He was totally surprised that they showed no reactions and talked very naturally about family or friends being killed.

In Bristol they picked up 3500 Army soldiers of color and took them to Manila, Philippines, traveling back via the Panama Canal. Bill remembers groups of soldiers singing hymns on deck. When the ship got to New Guinea, they were picked up by a group of ships that protected them on into Manila.

The ship spent 4-5 days in Manila. Bill also left the ship here, again in a group of not less than four. The Japanese had just been run out of the Philippines and there was lots of destruction. Leyte was a very bad area. Bill did a lot of walking around, sometimes 7-8 hours at a time, just reacting to what was there. People had been under Japanese rule for a long while and many did not talk to the U.S. troops. Bill remembers pigs and chickens in house yards and little children running out to him.

The next transport was taking the 1st Marine Division from the Philippines back to the U.S. On this trip they stopped in Ulithe because of Japanese submarine activity. It was here they heard that the war in Europe ended. The ship had been traveling without lights to avoid detection; but upon hearing the news, all the lights were put on and everyone celebrated. It was an honor to be carrying these Marines. They were the defenders of Guadalcanal, the battle that was the turning point of the war in the Pacific.

The ship stopped briefly in Honolulu, Hawaii, and then went on to San Francisco to unload the troops and get the ship checked out at the shipyard. From there, it was back to the Philippines. The ship was always on watch for mines the Japanese had planted and let drift in the ocean. They had to be shot and sunk before the ship could go on through the area. With the ship moving around in the waves and the mines bobbing up and down, it took a lucky shot to hit it.

Bill made four trips to Manila in all. All of his trips were safe. They weren’t “fun” but it was satisfying to bring troops home who had been doing the fighting.

Bill got no leave time during his enlistment. At the end of the 4th trip to Manila, he finally got to go home. The war in the Pacific ended so he then reported to Seattle and was discharged there. He hadn’t seen his family for two years. He doesn’t have many photos of himself in uniform because cameras generally were not allowed. Bill says you had to live with the war and live with whatever opportunities were at hand. He would do it again because of the circumstances. Did he think about staying in? “No, never.”

In thinking back, Bill says, “young people aged 18, do not have to decide what to do with their lives. They should take opportunities and use them. Two to four years of military service is the greatest opportunity in their whole lives. I wish all young people today would have that experience.” He says mothers sometimes don’t want their sons to go into the military, but young men can’t let their families decide for them.

Bill used the G.I. Bill (a law that provided a range of benefits for returning war veterans) to go to the University of Washington for forestry in 1951. He spent summers in Glacier Park, which is how he came to move to Montana.

Thank you for your service, Bill.