Lake County Drug Court honors first graduate

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

POLSON – Karen Tromp figured life as she knew it was over a year ago. She was in her 60s and set to go to prison after being charged with a felony for possession of dangerous drugs. A 45-year-old addiction brought her to this point.

She said she was a functioning addict for many years. She had a home and raised horses with her husband, but when he died in 2011, the loss sent her on a downward spiral.

She was caught with methamphetamine in 2014 and put on probation. She figured she would “play the game” and get clean long enough to take mandatory drug tests. “It’s what most people do,” she said. “But my luck went south, and I was busted again in May of 2017.” Tromp sat in jail and didn’t expect to be released.

As it turned out, her luck wasn’t as bad as she thought. District Court Judge James Manely and several supporters were developing a new drug court in Lake County. As a nonviolent offender, Tromp fit the criteria for the program.

Tromp said something clicked in her mind when she heard about the program. “I wanted to do this,” she said. “I wanted the help. I had a life and a family to get back to. When you are my age, spending even a few years in prison is like a life sentence.”

Manley said the program was created as an alternative to traditional incarceration in the county for some drug related crimes like possession. “The old system isn’t working,” he said.

In 2013, the felony filings in the county jumped from about 220 cases a year to almost 600. “The increase is due entirely to the drug epidemic and drug-related crimes,” Manley said.

He said putting someone in prison costs about $34,310 a year for men and $42,500 for women. The in-patient treatment programs cost even more.

The cost of a felony drug case includes more than jail time. He estimates the total to be around $100,000 per person including the cost of police, prosecutors, defense attorneys, the judge’s time, treatment, and parole. He said 500 new felonies a year cost $50 million.

“Those costs are spread through many agencies so we don’t see it, but, to put it in perspective, that is about the amount of the total budget to run Lake County government and the Polson School District, put together. That money comes entirely from local property taxes and state income taxes,” he said.

The human cost is another factor in the equation. He said most of the offenders are parents or grandparents. “If they are sent to prison and come out with the same addictions, their children suffer, if they have not already been placed in the foster care system,” he said.

Manley started looking for a better approach. He formed a drug court team to find a solution with a prosecutor, defense attorney, parole officer, chemical dependency counselor, tribal councilwoman, drug court coordinator, the undersheriff, and a drug-testing specialist. The group traveled all over Montana to study other systems. “We worked hard for a year with no pay,” he said.

The team learned that drug courts, as opposed to regular sentencing style court systems, were having success rates in the range of 60 to 80 percent. He wanted to have a program like that in Lake County, but funding it was a problem.

The group looked for grants and received one for $50,000 from the Gianforte Family Foundation. It was enough funding to hire a coordinator to start organizing the program. At the beginning of 2018, a grant came in from the Federal Justice Department for $399,000. The money is to be spread out over three years ($133,000 each year).

Tromp was one of the first people approved to participate in the program. She said it wasn’t easy. She attended drug court once a week, went to three counseling sessions a week, and attended three self-help sessions each week. She needed to participate in community service activities, and have random drug tests done. The program also requires a person to be employed and find sustainable career options or education and training. A small $15 accountability fee is tacked on to the requirements to help pay for drug testing.

“They gave me a second chance,” Tromp said. “But, I had to work at it, and I did everything. I learned that I want to be a good citizen. I deserve a good life.”

After a year of counseling, she said she discovered that it’s important to ask for help, and look to a higher power. “It doesn’t have to be God,” she said. “It’s whatever that means to you. It’s something you look to when you feel triggered.”

She said developing a support system has been the most important aspect of her treatment. She has counselors, friends, family, and a judge on her side.

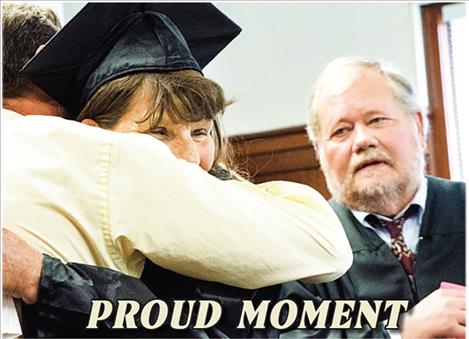

Tromp was so successful in her program that she completed it in about a year. The program can take anywhere from 12 to 24 months to complete. She stood in front of Judge Manley on Thursday, May 17, and instead of going to prison, she received a certificate, and became the first Lake County Drug Court graduate.

She turned to the audience in the courtroom after thanking the judge and said: “This program works, but you’ve got to want it.”

Twelve people are currently attending the program with two to four new enrollees accepted each month. Manley hopes the numbers increase as the program develops.

An evaluation team was sitting in the courtroom taking notes as part of the Federal Justice Department grant requirements. The results won’t be ready for at least 45 days. Judicial candidates were also in the audience to watch the process. It was stated that they are all in favor of the program.

Manley looked out at the audience. He said courtrooms are traditionally set up as places of intimidation. The room is often dark and the tone is serious. The judge wears a black robe and looks down on people. He wants drug court to be different, although he can’t change the room. He did make the tone friendly and inviting with words of encouragement and several hugs.

“We are trying to build more confidence here,” he said. He wants participants to feel valued and positive about the experience, so they achieve their goals.

He later said: “The most surprising thing for me is how much I have come to know and like our drug court participants. When you get past the addict stereotype, you learn that these are good people who are trying very hard to get better.”

Before Tromp graduated, the other program participants went in front of the judge to talk about how they were doing as part of their requirement. Their full names are being left out of this story to protect their recovery process.

One woman was excited to report that she was creating a stable life to help support her grandchildren. “This is an amazing program,” she said. “I’m just sorry it took me so long to get started.”

Todd came forward to say he was having a good week. His family was doing well. “If it weren’t for this program I’d be locked up in jai,” he said.

Dolores said she hadn’t been sober since she was 15, and she hadn’t ever received a paycheck. She was proud to report that she was sober for 193 days and had a job. “If it weren’t for drug court, I’d be dead,” she said. Tears filled her eyes as she said she wished everyone with addiction problems could have access to the program.

Another woman was on a continuous cycle that included using drugs, being caught, going to jail, getting out, and using drugs again. She wanted something different this time.

Manley looked at her and said the program isn’t easy. He doesn’t “expect perfection” from participants because beating addiction is difficult, but he does want them to try as hard as they can, and not just go through the motions needed to participate.

Manley said the next participant standing in front of him was “proving everyone wrong” with 67 days of success. The man said when he first joined the program, he thought he could “sneak by” and get clean enough for the drug tests, but this program gave him the support he needed to work through it.

Ricco reported to the judge that he was 331 days clean. Manley asked if getting clean was something he could have done without the program. “No, not at all,” he answered. He said the program forced him to be honest and accountable. He said he discovered that he had the right to a sober life, and he wanted to keep with it. Several other participants reported the days they’d been clean with the drug tests to prove it.

Jay Brewer, local addiction counselor, is working with drug court to help participants. He congratulated Tromp. He said that her success shows that after 45 years of using, drug court can work. After graduation, participants are called on a regular basis, and resources are available if they need more help.