Phil Jackson supports preservation of Flathead Lake

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

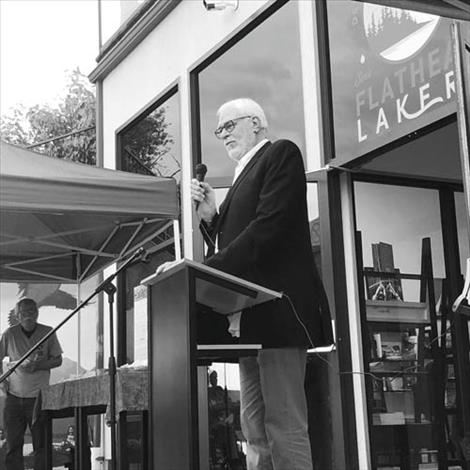

Unceasing change was the theme of basketball giant Phil Jackson’s talk to the Flathead Lakers last Friday in Polson. The Montana native, who played as a power forward with the New York Knicks before leading the Chicago Bulls and Los Angeles Lakers to a combined 11 NBA titles, recounted his long history with Flathead Lake.

Born in Deer Lodge, Jackson first encountered the Flathead along the Middle Fork, where his parents built a cabin and he caught his first fish with a bamboo pole. In the early 1970s, during his years with the Knicks, he returned via motorcycle. “I always seemed to end up here,” he said.

In 1973, while camping at West Shore State Park, he heard about a piece of property for sale nearby, owned by a Union 76 dealer. Fifty-gallon oil drums served as a cistern, and a pipe “shoved into the lake” supplied water to the cabin. When the Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks found fecal matter in the bay in 1975, the neighbors got together and decided to drill wells and build septic systems.

In the 1980s, as co-owner of Second Wind Fitness Center in Kalispell (now Summit Fitness) he recalls the emphasis on limiting phosphate pollution in the lake to preserve its clarity. And he remembers the shock people felt when the kokanee salmon fishery abruptly collapsed, due to the introduction of Mysis shrimp and the burgeoning population of predatory lake trout.

“All of a sudden they were gone,” he said of the kokanee. “But we move on because that’s unceasing change.”

He’s watched the nature of recreation change on his beloved lake, from water skiing, to wake boards and kneeboards, and now surfing behind “big boats with big sound systems.” He noted the recent success of community efforts to halt a proposed amusement park south of Lakeside, along a particularly treacherous part of U.S. Highway 93.

“That told me the community could really rise and support one another in these type of situations,” he said.

“Life goes on. We experience it for a few years and then retire from the scene and someone takes our place, our voices and our passion,” he said. Noting that his audience was mostly comprised of gray-hairs, he added, “Hopefully we can find somebody under 50 that will take our passion and lend it to the lake.”

Kate Sheridan, executive director of the Flathead Lakers, thanked Jackson for his long support of the organization. “We’re so lucky you’ve chosen to join this Lakers team as well,” she said.

Sheridan went on to introduce Dave Hadden, who received the organization’s Stewardship Award for “extraordinary achievement” in his efforts to protect Flathead Lake and its watershed. Hadden began his work in conservation in the 1970s, working to protect the North Fork of the Flathead, and his efforts expanded to encompass the Crown of the Continent ecosystem.

He was part of an international team that thwarted efforts to build a mountaintop removal mine at the headwaters of the North Fork in Canada, and was involved in negotiations that led to the final passage of the North Fork Watershed Protection Act in 2014. He’s since worked to limit selenium discharges from mining operations that contaminate the Kootenai River, and helped launch the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative that connects and protects habitat from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to Alaska.

Although recently retired, Hadden remains active in efforts to prevent an oil-train derailment along the Middle Fork of the Flathead, which he describes as a “profound threat” to the Flathead basin.

“I think the Lakers are in a position to lead on this issue and they should be the point of the spear,” he said.

Dr. Jim Elser, director Flathead Lake Biological Station, wrapped up the meeting with his annual State of the Lake, which he described as “full of water, blue and mussel-free.”

He recapped the past year, noting that the station lost a beloved cook to COVID and had to cancel the 2020 summer session for the first time since World War II due to the pandemic. The recent Boulder 2700 fire forced the station to evacuate this year’s crop of students to the University of Montana campus in Missoula, where they were able to complete their summer studies.

“It was a challenging and frightening night to muster 30 students with the glow of the fire on the horizon,” he said. Despite the conflagration, the monitoring team still managed to collect water samples that week.

On a positive note, Elser said DNA samples from around the lake show no sign of the dread zebra mussel, although “a record number of infested boats have been stopped already at inspection stations.”

As more and more people bring watercraft to Montana from other states that are infected with the mussel, “we must not relax our efforts.”

Forty years of data reveal that the level of phosphorus – which diminishes water quality and leads to algae blooms – remains “relatively stable” in Flathead Lake, even as it’s increasing in lakes and waterways across the U.S.

“It’s because we’re taking care of our poop and pee,” he said, noting that several communities, including Polson, have built advanced wastewater treatment facilities. Replacing aging septic systems and installing pump-out stations for boats are crucial to maintaining the lake’s clarity and water quality, he said.

Elser pointed to the recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that “makes it very clear that climate disruptions due to greenhouse gases are already upon us. Climate change is not an abstraction any more, it’s something we’re living in.”

The scientists at the biological station continue to monitor the temperature of the lake and study the small lakes and streams that are appearing as glaciers disappear from the high country.

“We’re watching everything very closely, scientifically, analytically,” he said. “But we’re people, so we’re also watching with emotions of fear, anger, concern, worry, sadness.”

He counseled the crowd to avoid despair and inaction, however. “We must realize we can still take concrete actions to avoid the worst outcomes.”

Elser encouraged people to find ways to transform transportation systems, power generation and agricultural practices.

“Water unites us all,” he said. “It unites us around this magnificent lake and it unites us with our ancestors who also gathered around this lake to enjoy its beauty and its clean cool waters. Protecting this lake is one of the most important ways we will be united with our descendants, so let’s be good ancestors.”