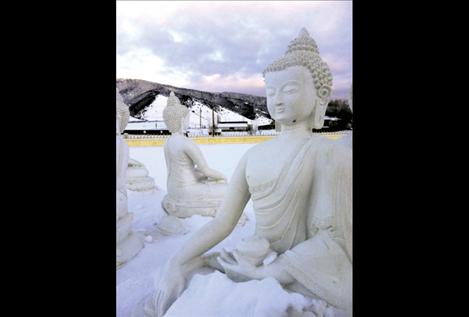

Buddha garden set to ring in Tibetan New Year

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

ARLEE — If you couldn’t find your New Year’s Eve kiss this year, have no fear, the Tibetan New Year is almost here.

And according to the Tibetan calendar, it’s still 2012. Feb 11 marks the first day of Losar (the Tibetan word for “New Year,”) and the first day of 2013.

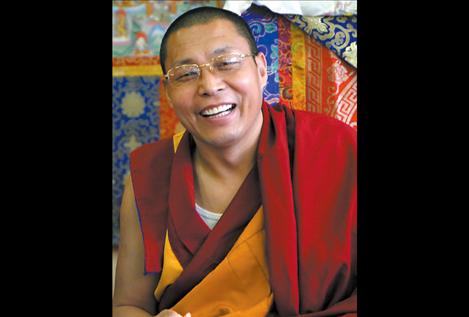

Namchak Khenpo, a Tibetan Buddhist monk and brother and spiritual heir to Tulku Sang-ngag Rinpoche (the founder of Ewam’s Garden of 1,000 Buddhas,) is the resident abbot at the garden in Arlee. He spends much of his time in either Nepal or Montana and remembers the Losar celebrations of his childhood in Tibet quite well — as a child, he could barely sleep the night before the big day.

As Khenpo does not speak English fluently, his friend and translator Khenpo Sonam served as an intermediary during a phone interview.

According to Namchak Khenpo, the first King of Tibet was enthroned in 127 BCE. The Tibetan new year celebration actually began with Pude Gungyal, the ninth King of Tibet.

“Back then, they didn’t really have a standardized lunar calendar,” Khenpo explained.

Each year, when the peach trees blossomed on the Yarlha Shampo mountain in Tibet, the Tibetans would gather and celebrate to welcome the new year during the spring. However, sometime in the seventh century, all of Buddha’s teachings were translated into Tibetan. This created a wealth of knowledge from which to draw.

The shaman tradition of Tibet had a way of calculating time, taking into account the changing seasons and the many phases of the moon while creating their calendar. By incorporating aspects of the Indian and Chinese calendars, the Tibetan new year celebration was eventually moved into February.

“In that way the Tibetan calendar became standardized,” Khenpo said.

The actual day of Losar moves from year to year because the calendar remains primarily based on lunar cycles. These cycles do not match up with the 365-day calendar to which most Westerners are accustomed.

For example, according to the Tibetan calendar, a month can have between 28 and 30 days, depending on the size of the moon, and a year can have up to 13 months. In addition, we are still in 2012 and, “(Jan. 12 was) the first day of the last month of 2012 — the year of the water snake,” Khenpo said.

The celebration traditionally lasts three days. Before the first day of the new year, family members gather water from nearby rivers, lakes and streams and fill every vessel in the home while praying for a good year, prosperity, health and auspiciousness.

“Water coming through the tap is a modern thing, but in the past, people had to go fetch water from the water spring or source and make an offering by burning herbs and sages and smearing butter near the water source in gratitude, which is given as an essential offering.” Khenpo explained.

Next, Tibetans make a soup from barley flour. “Dro,” the Tibetan word for barley, “Is a word of excellence,” Khenpo said. “It means beneficial and excellent, so they make a soup out of barley flour and that is the first thing they eat.”

In addition, the word for “head” in Tibetan means beginning, so in the past, on the first day of Losar, Tibetans would eat the head of a lamb that had been stored from a recent slaughter.

“On the first day, you do everything that is excellent and you make offerings that are all excellent; you wear clothes that are nice; and you eat food that is beneficial and excellent; and in the past, you would eat the head of a lamb that was saved for the new year to have a good beginning,” Khenpo said. “That was the traditional way to do it.”

Today, modern Tibetans sculpt a lamb’s head from butter and set it upon a pile of barley flour. As part of the blessing, three pinches of barley flour are thrown into the air above the butter sculpture. The fourth pinch is eaten while they say, “Tashi Delek,” or, “May excellence be there.”

In addition, families will sculpt intricate shapes (like flowers) from dough and fry them. These are eaten along with the barley soup.

“So, on the first day, families and children and parents will get together and stay together, eating good food and drinking alcohol. Stay close, good food, enjoy, celebrate,” Khenpo said.

On the second day, relatives will travel to their friends’ homes and have a similar gathering.

On the morning of the third day, everyone in the village gathers together and hikes to the top of the nearest mountain or sacred place, because “every village has a mountain or sacred place,” Khenpo said.

Once at the top, the villagers build a fire and burn incense, while the monks pray and hoist Buddhist prayer flags onto trees or hang them from the sides of cliffs.

“This is for a small village,” Khenpo said. “If it is a large town, the celebration could last for more than a week, depending on the size of the family and the number of friends.”

As a boy, Khenpo said Losar was a very special day and he would be excited and anxious a full two to three months in advance.

“On New Year’s Eve, I wouldn’t even go to sleep because the next day I would get to play as much as I wanted,” he said.

Tibetans calculate a person’s age by the year they were born. For example, 2012 was the year of the water snake, and 2013 will be, the year of the water dragon. So, if you should ask a Tibetan when he was born, he is likely to respond somewhere along the lines of “the year of the water snake.”

Because Tibetans keep track of age this way, everyone’s birthday is New Year’s Day. Khenpo joked that the older he gets, the more Losar reminds him of aging.

“For older people, New Year’s is not as exciting because they are getting a year older,” he said. “But, every year is an opportunity for me because I am a practitioner and follower of the Buddha, so every year is a new chance to achieve ascent to enlightenment.”

The Garden of 1,000 Buddhas will host a three day Tibetan New Year weekend running Feb. 9-11. The retreat costs $150 for food, lodging and teachings, but no one will be turned away due to lack of funds. Those wishing to attend are encouraged to register in advance with Amy Chalcraft by calling 726-0555 or by emailing admin@ewam.org.