Proposed threatened species listing could affect wolverines

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

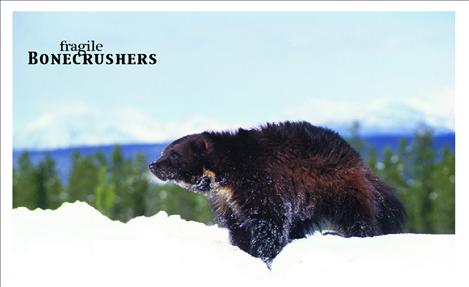

MISSION MOUNTAINS – In many ways the wolverine is nature’s original mountaineer. The large weasels rarely exceed 35 pounds, but have the capability to ascend entire mountains in a couple hours’ time, crush bone that is frozen solid, strangle polar bears to death, and nestle into homes constructed from frozen water.

“I think most Montanans appreciate wolverines for being complete bada——,” is how wildlife activist Matthew Koehler describes the public’s perception of the creatures.

But scientists project a clear winner in the ongoing fight between the ferocious animal and a silent, invisible enemy sweeping across Arctic and sub-Arctic lands, slowly suffocating the habitat ranges of many northern species. In the showdown battle of wolverine versus climate change, warmer temperatures are expected to prevail, and severely reduce the amount of snow that falls in the lower 48, where an estimated 250 to 300 of the animals rely on yearly snow pack to raise their young.

In 2010 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service cited climate change as the primary reason the wolverine should be listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act, but Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks disagrees that the designation is necessary. A decision from the Fish and Wildlife Service could come as early as Aug. 4 and would impact an unknown number of wolverines in Mission Valley.

“They are an animal that is tougher than nails, but at the same time is extremely vulnerable,” Jeff Copeland, executive director of the Wolverine Foundation, said.

Home on the Range

There are an estimated 15,000 to 30,000 wolverines alive on Earth today, mostly in the extreme northern parts of North America, Europe, and Asia. The animals once lived as far south as mountain ranges in California and Colorado, according to Copeland. The creatures all but disappeared from the contiguous United States in the 1930s, but reappeared three decades later. Wolverines continued their southward push into fragmented climates at high elevations where snow is plentiful in the winter months.

An individual with a tracking collar dubbed “M56” made it all the way to Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park in 2009, where a photographer snapped a photo of it. It was the state’s first confirmed report of a wolverine since 1919. Other individuals with tracking collars have made it all the way to California, but established populations are found only in Washington, Montana, Idaho and Wyoming.

The animals typically scavenge from carcass to carcass, and that has likely played a role in their renewed push southward.

“Thinking about the low densities at which they live and their ability to persist … The grizzly bear couldn’t do it. The wolf couldn’t do it.” Copeland said. “They have this almost insatiable need to move.”

Travel for wolverines is much different than travel for humans. Where people plan the path of least resistance, wolverines barrel through and go up and over. The stubbornness can be a great asset, but also might make the animals less likely to adapt their reproductive tendencies, which is dependent on deep snow.

Wolverines mate in the summer, but fertilized eggs don’t implant and begin to grow until winter. Females go into snow dens in February where kits are born and raised until they are weaned in May. Females don’t reproduce until they are three years old and bear one to three kits per litter. A mother will not necessarily have a litter every year, although it is possible.

“Their reproductive rate is low,” Copeland said. “We’re commonly asked ‘Can wolverines adapt with less snow?’” Copeland said.

If wolverines had an ability to raise kits outside of snow dens, scientists likely would have observed it at one of 700 dens that have been monitored and studied worldwide.

“If they have that adaptive capacity, we should see it happen,” Copeland said. “And we never have.”

In 2011, the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. projected summer temperatures for wolverine habitat will likely rise over the next eight decades from a current average of 72 degrees or lower — with rare 90 degree days — to much higher temperatures where 90 degree days are the norm. The overall habitat for wolverines is expected to shrink 63 percent by 2099.

While listing wolverines as a threatened species might not solve the climate change crisis, Copeland believes it could benefit the species.

“One thing we know for sure is that animals receive attention when there is public interest in them,” Copeland said. “Saying we can’t do anything is incorrect. It will get attention. It will be mandated that it gets attention. If it’s not listed (as a threatened species) it will get no attention.”

Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks opposes the listing.

“We don’t believe that suggesting (that) global climate warming will affect habitat years down the road should mean the wolverine is classified now,” Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks spokesperson Ron Aasheim said in a recent telephone interview.

The state also argues it is effective at wolverine management.

“We really believe that wolverines are in good enough shape in Montana that the state should manage them,” Aasheim said.

Aasheim points to the reduction in state’s trapping quotas for the species over the years as a testament to Montana’s management success. Wolverine pelts are highly prized and often used as trim for parkas, according to the Montana Trapper’s Association. According to Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks, wolverine fur fetched the second highest price of all animal pelts of legally trappable species, just a tad lower in value than bobcat fur. The average price of a wolverine pelt in 2012 was $319.67. Until recently, the Treasure State was the only one of the lower 48 states to allow harvest of wolverines.

Prior to 2008, up to 10 wolverines were allowed to be trapped in Montana each year. In 2008 the quota was lowered to five animals. There were no wolverines trapped in 2012 or 2013, Aasheim said.

It wasn’t Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks that gave wolverines a reprieve. A state district court judge closed the season in November 2012, one day before trapping was set to commence. After hearing oral arguments in January 2013, the judge sided with a group of six environmental and conservation groups that sued to close the trapping season until the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issues its decision about the threatened species listing. The listing would permanently close hunting season, but unlike other species, the wolverine’s listing would not impose limits on recreational or economic activities in the wolverines’ habitat such as snowmobiling or forestry. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service wrote that these activities likely had little impact on the species in its petition for listing.

The decision to close hunting strikes Koehler as a no-brainer.

“We have an Endangered Species Act to protect species from going extinct, and if there are 250 to 300 individuals left in the lower 48 are we going to wait until there are 50 wolverines left, or maybe 10?” Koehler said. He is the executive director of the WildWest Institute, a Missoula-based group focused on protecting and restoring America’s forests and wetlands. In 2012 the group intended to file to close wolverine trapping season along with the other environmental advocates, but missed the deadline.

Koehler said some biologists estimate the state’s number of breeding-age wolverines that are within range of an eligible mate might be as low as 35 individuals.

“If we had an effective elk population of 35, would Montana still hand out elk tags?” Koehler said. “It’s a question we need to ask.”

For dissenters who doubt trapping can make an impact on population, Koehler references a 2007 trapping study conducted in the Pioneer Mountains of Idaho where biologists collared 14 wolverines. Six of the wolverines died in traps over a three-year time span. Among the dead were four breeding-age males and two pregnant females.

Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks has a different opinion.

“We believe we have a healthy enough population to have a conservative trapping season,” Aasheim said. Fish Wildlife and Parks does not have any intensive research efforts underway that are focused on wolverines or the effect of climate change on the species, although it does log any tracks found during annual track surveys, according to Aasheim.

In December, a third comment period for the wolverine’s proposed listing ended, and a decision appeared to be forthcoming, but Montana and other states asked the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for another review of the data.

“What we’re looking for is an opportunity for an independent panel to have a chance to look at the scientific evidence,” Aasheim said. “Let’s not get in a hurry here, let’s take a look at the science and decide what is best for the species.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife granted the request and imposed the Aug. 4 deadline for the final listing determination.

Mission Mountaineers

Montana is the last holdout state in the lower 48 for trapping wolverines, but concern for the creatures has been brewing much longer on the Flathead Reservation. Twenty years ago, the Confederate Salish and Kootenai Tribes closed the trapping season for the animals, which tribal ancestors described as secretive, according to CSKT Wildlife Program Manager Dale Becker.

Although the animals have been left alone on the reservation, they remain elusive.

In March 2011, David Evans and Associates issued a memorandum that stated wolverines had not been sighted in Lake County since 1966, and there were only 14 recorded sightings since 1952. The memorandum detailed a biological impact study for the construction of Skyline Drive in Polson. It cited the Montana State Historical Project, which collects data from the Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks harvest numbers, U.S. Forest Service surveys, and Glacier National Park observations.

The project does accept sighting submissions from the public, according to data wrangler Scott Blum.

While it is unlikely that wolverines are living along the area where the project was completed, there is significant evidence that the gritty weasels are flying under the radar in some of the most remote parts of the county.

In 1996 Koehler was backcountry exploring on the Forest Service side of the Mission Mountain Wilderness just below Pass of the Winds, near Gray Wolf Lake with friends when they spotted a wolverine that went in the opposite direction.

“It was unmistakable what we saw,” Koehler said. “I always thought I was pretty lucky to see a wolverine.”

Germaine White, spokesperson for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Department of Natural Resources, also saw a wolverine near Ronan a few years ago. White had seen wolverines in the Arctic prior to the sighting and she said encountering the same species near Ronan was at once disconcerting and exhilarating.

“It was just loping along,” White said. “It seemed to be completely unconcerned by my presence. It was pretty remarkable.”

The most concrete sign that wolverines persist in the Mission Mountains is a pair of YouTube videos featuring game camera footage of two wolverines at bait stations in 2013. The videos were posted by Northwest Connections, a Condon-based group that is working with the United States Forest Service and the multi-agency Southwest Crown of the Continent Collaborative to conduct carnivore surveys in an area encompassing Swan Lake toward the south to Seeley and over to Lincoln.

Biologist Adam Lieberg said the group will continue to conduct the carnivore surveys this winter. The surveys include bait stations that are armed with gun brushes meant to snag fur while the animal chows down on grub. The hair is then sent off to a laboratory where DNA analysis determines whether or not the animal was a lynx, wolverine or fisher. The DNA results of the 2012 survey are expected to be completed this winter. Although no one working the surveys has seen a wolverine in person, video footage, photographs and tracks confirm they are in the area.

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes also monitor wolverines in the area, Becker said. Aerial and track surveys have confirmed that wolverines lived on the reservation, but wildlife management wants to know more about the species.

Wolverine, mountain goat, and grizzly bear are of particular interest to the Tribal Wildlife Program because of the threat of climate change. The tribes adopted released an 83-page strategic plan to handle climate change in September. The document is the first step to tackling the warming phenomenon’s impact on natural resources and cycles that include fire season and habitat patterns.

“It’s a matter of funding,” Becker said. Grants writing for projects that could help the tribes monitor wolverines are in the works, but are only in the beginning phases.

It is unclear whether or not listing as a threatened species or efforts of the tribes will save the wolverine in the end, but for Becker, trying to protect species from disappearing is a matter of conscience.

“Do you just brush them off the edge?” Becker asked. “I think all life forms are here for some reason. Some will adapt quickly. Some won’t. But there will be some things we maybe can do and we should do, because the impact of climate change on people is not far behind. If we can’t step back and do some planning, then that doesn’t say very much for us as a species.”

Becker asks that anyone who spots a wolverine or its sign contact the Tribal Wildlife Program in Polson at (406) 883-2888, ext. 7278.

The Wolverine Foundation also has a form on its website to report wolverine sightings. The Foundation accepts photos, hair, and feces as supporting documentation for the sightings.