Volunteer readers bring Martin Luther King’s time to life

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

PABLO — The ‘60s seem far away in the past to grade school children, and sometimes they don’t understand civil rights and the importance of historic leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr.

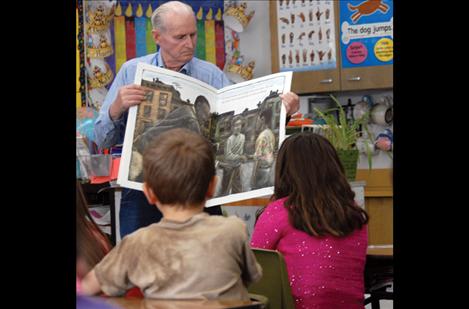

Foster Grandparents and community readers came to Pablo Elementary School Jan. 20 to make King’s quest for civil rights more understandable to students.Volunteers talked about their own experiences and read students stories about King, his life, and his fight for civil rights.

Readers were Billie Lee, Mary Parsons, Ray Salomon, Pat Wenzinger and Cindy Willis.

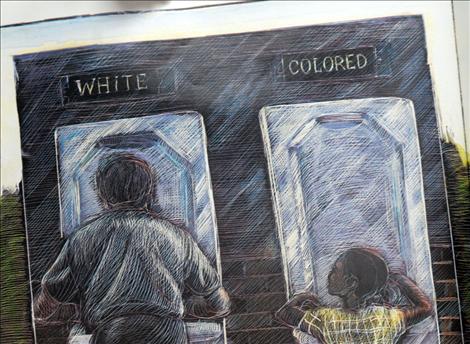

A member of the Foster Grandparents program, Wenzinger lived in Ohio as a child but had relatives in the south. There was “white town and black town” and “white school and black school,” Wenzinger said. “It’s just the way it was.”

When she was a student at Roosevelt Middle School in Middletown, Ohio in 1946 or so, Pat recalls a new student coming to school, a black girl. Wenzinger made friends with the young girl, but soon she quit and attended the black school. A southerner, Wenzinger’s mom was glad because she didn’t want Wenzinger having anything to do with the young girl.

Wenzinger relayed an experience with the Mason-Dixon line, “an invisible line.”

As a young girl, she was accompanying her mother on a train trip when the train went out of Cincinnati and crossed the state line into Kentucky. Immediately the conductor came up and asked a black woman sitting near Pat and her mom to move to the back car, which is where black people were supposed to sit.

As for employment for black women as servants, Wenzinger said Kathryn Stockett, author of the novel “The Help,” got it “right on.”

Willis recalled being one of the 250,000 people who came when King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech, although she was so far away she couldn’t see or hear him.

She also was a freedom rider before there even were freedom riders. At the age of 17, Willis took a bus from Michigan to Louisiana to visit her family. A black lady took Willis under her wing, and the two women accompanied each other to restaurants, bus changes and bathrooms as the bus headed south.

In Jackson, Mississippi, everything changed because Willis’ friend couldn’t sit in the café with her; she had to go to the colored café. Willis was incensed; she’d grown up in a military family with no prejudices so she joined her friend in the black café.

“It isn’t a black and white issue, it’s an issue of equality,” Willis said.

Willis and Lee read “My Uncle Martin’s Big Heart” by Angela Farris Watkins, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s niece.

Using eye color as an example, Willis asked the kids if someone with blue eyes could say they were better than someone with brown eyes.

“Is it fair?” she asked the children.

A resounding “no” came from the third-graders.

After hearing stories about King’s dream, part of which was, “I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but by the content of their character,” kids were asked about their dreams.

Andreas Kenton, a first-grader with a shy, no-front-teeth smile, said, “My dream is to be a teacher.”

Classmate Kaden Le Grow’s dream is to be in the army, he said.

Both career paths can affect change.