Cooperative craft breweries: a new approach to revitalizing small towns

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

Small. Independent. Traditional. These are the words used to define a craft brewery. They could also be used to describe many rural towns across Montana and the Northwest. As small towns contend with big problems in the wake of ever-increasing urban sprawl, they’re getting creative in their search for solutions and sustainable futures. Capitalizing on the craft brewing craze as a way to revitalize small towns, is an idea that seems to be gaining in popularity. Community members in the small town of Ronan are looking to tap into the movement, but with a twist. The group is seeking to establish Montana’s first cooperatively-owned craft brewery.

About 12 miles south of Flathead Lake, the town of Ronan is a community based largely on agriculture. With several schools, banks, a golf course and an active business community, Ronan is home to an estimated 1,871 people (according to 2010 U.S. Census information.) But while it boasts a variety of businesses, including a telephone company, a movie theatre, a café, a thrift store, a bowling alley, hospital, and others, many Main Street storefronts remain empty or rundown. Roughly a third of Main Street buildings are vacant or in disrepair.

Through several public listening sessions held with economic developers in 2016, community members identified the revitalization of Main Street and increased business development as priorities for their town. With a cooperative development center on Main Street, eventually the idea of a cooperative brewery emerged.

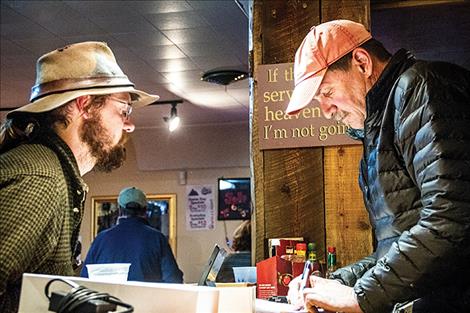

A year and half later, 100 or so people gathered at a Ronan bar on a Saturday night as would-be owners of the Ronan Cooperative Brewery. The Ronan Valley Club buzzed with energy on Dec. 2 as friends, neighbors and strangers connected over a cold drink and an idea. The gathering was the first public event of an ownership drive currently underway for the proposed brewery.

“I was kind of wondering what would happen,” steering committee member Gail Nelson said as he surveyed the room with a smile. “I’m excited by this.”

Gail’s wife Barb, who also serves on the steering committee as chairperson, agreed.

“You can feel the excitement in the room,” she said. “I think we can do it. I really do.”

Groundwork

Brianna Ewert, cooperative development program manager for Lake County Community Development Corporation’s Cooperative Development Center provides technical assistance to Ronan Cooperative Brewery’s steering committee.

Ewert, who’s been involved in the project from day one, said the idea for a brewery came about early in Ronan residents’ discussions with economic developers.

A year after identifying Main Street revitalization and business growth as priorities for Ronan, a public meeting was held and survey conducted to gauge community interest in a co-op owned craft brewery. Both revealed a broad base of community support for the project.

A nine-member steering group formed soon after to determine feasibility, write a business plan and structure the cooperative.

Following a feasibility assessment in which costs, potential profits, customer base (including town residents and tourism data) was analyzed, the Ronan Cooperative Brewery filed an intent to incorporate with Montana’s Secretary of State. Incorporation will be finalized once a phase I goal of $75,000 in shares sold is met. Steering committee members anticipate meeting that goal in January.

“The idea behind the Ronan Cooperative Brewery is to bring together a strong craft beer movement to help in the revitalization of our community,” an ownership information brochure states.

Two classes of shares, common stock and preferred stock, are being sold. Common stock is $250 per share. All members purchase one share which gets them one vote. Additional shares do not garner additional votes. Preferred stock, offered to common stock members, is sold at $100 per share. Preferred stock yields a member more of a share in the return down the road as the brewery becomes profitable.

Upon incorporating, a meeting would be called for members to organize, elect officers and approve bylaws. The newly elected board of directors would then transition to managing operations.

The economics of craft brewing

Montana has 68 craft breweries – independent entities that produce relatively small amounts of traditional or innovative beers, according to 2016 data compiled by the Brewers Association. It ranks second in the nation for breweries per capita. The state’s craft beer production has increased at a rate of roughly 13 percent per year since 2010, the Association says.

That growth has produced economic impact. Kyle Morrill, a senior economist at the University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research, says that 1,044 additional permanent year-round jobs, more than $33 million in additional income for Montana households, $103 million in additional sales from businesses and organizations and an increase to the state’s population by 280 people are attributable to brewer operations.

“Craft brewing represents a sizable, grass-roots industry to the Montana economy,” he wrote. “Furthermore, brewpubs often appear in historically industrial neighborhoods, reinvigorating and reimagining properties left vacant by passing industry.”

Montana’s brewers are poised for further growth as during last spring’s legislative session, the production cap was raised from 10,000 to 60,000 barrels a year.

Cooperatives

Cooperatives are organizations owned collectively by members who share in profits or benefits.

While craft breweries aren’t a new phenomenon, co-op owned breweries are. With only a handful in existence in the United States, the model of co-op ownership is unique.

In addition to serving as the local cooperative development program manager, Ewert has been a member of several cooperatives and is currently working to finish her certification as a cooperative development specialist.

Cooperatives, she said, have a large economic impact both on a national and state scale, generating $650 billion and $1 billion in revenue respectively.

As a whole, cooperatives tend to return more money to the local economy and generally generate more jobs for the same amount of sales, she added, and, according to research done in Canada, co-ops have twice the survival rate of corporate businesses.

As opposed to a corporation’s mandate to maximize profits, the end goal of a cooperative is to serve its members.

Ewert credits this critical difference in structure, of membership deciding how their needs are best served, as the reason cooperatives tend to be more resilient.

Los Alamos

Los Alamos, New Mexico, is one place the co-op model of brewery ownership seems to be working. April 2018 will mark the three-year anniversary of Bathtub Row Brewing in Los Alamos, and according to general manager Douglas Osborn, “things are going very well.”

So well, Osborn said, that the brewery continues to grow at a rate of 10-20 percent annually and is on track this year to hit $700,000 in sales.

After 2 1/2 years in operation, the brewery will begin to pay back its loans this December and is on track, Osborn said, to become debt free within the next three to five years.

Production wise, the brewery operates at almost full capacity and at times can’t make enough beer for their guests.

“It’s a good problem to have,” Osborn noted. “We’re far past the original projections.”

During times when they can’t produce enough beer for customers, Bathtub Row Brewery purchases beer from other New Mexico craft beer distributors. In fact, Osborn said the brewery has great relationships with its competitors.

Though they don’t serve food, Bathtub Row patrons are welcome to bring food in with them or purchase meals from nearby restaurants or from vendors who set up their hot carts at the brewery.

The brewery, which employs 15-17 people, has also seemed to spark growth for other nearby businesses.

“The Mexican restaurant next door is doing very well since we moved in,” Osborn said. “And they’re putting up a pizza place right across from our parking lot.”

Osborn readily admits that there are both advantages and drawbacks to cooperatives.

There are times when it’s cumbersome, he said, to work through problems via committee. On the other side of that, he said, having a lot of people to rely on for help or to bounce ideas off of, is a benefit. He also credits low employee turnover to the co-op model of ownership as employee-owners have more of a vested interest in the brewery’s success.

“Overall, it’s a huge plus,” he said.

Bathtub Brewing has two different kinds of memberships – annual and lifetime. Annual members pay $50 a year and don’t get to vote but do get discounts on beverages and merchandise. Lifetime members pay a one-time fee of $250 and can vote on brewery business.

Osborn estimates that of Bathtub Row’s 1300 or so members, half are annual and half are lifetime.

In order to accommodate their membership, the brewery rents out the local theatre to review annual financials. A smaller board of directors, seven, hold monthly meetings with the general manager and head brewer to oversee operations.

According to Osborn, Bathtub Row has about $40,000 worth of shares left to sell before they run up against what their charter allows.

On the horizon

A successful Dec. 2 ownership drive has poured new money and energy into Ronan’s Cooperative Brewery.

More than $26,000 was raised and 48 new owners signed on, tipping the total in shares sold to $52,350. As the business plan is currently written, once $150,000 in owner investment is reached, that money would be used as leverage for additional loans.

As of mid-December 2017, the total of all funds raised, including development funds that have been awarded the project, was more than $75,000. The number of Ronan Cooperative Brewery owners was 125.

While there isn’t an official target date, steering committee chair Barb Nelson believes the brewery could be operational as early as Sept. of 2018. Additional ownership drive events have been planned for Tuesday, Jan. 16 from 5 to 7 p.m. at the 44 Bar and Outback Café in St. Ignatius and Saturday, Jan. 20 from 5 to 7 p.m. at the Vine and Tap in Polson.

LCCDC Food and Ag Program Coordinator Rosie Goldich said she was encouraged by the number of Ronan Main Street business owners who attended the Dec. 2 event.

“It’s nice that downtown Ronan is here, represented tonight,” she said. “We’ve had amazing community support for this project.”

While most in attendance were Ronan residents, some came from neighboring towns and at least one man made the trek from Missoula.

Toby Hubbard, former owner of the University Motors Honda dealership in Missoula, said he heard about the event through Facebook.

Looking for an investment opportunity after selling his business, Hubbard said he saw investing in Ronan’s Cooperative Brewery as a way to “help the community and make a little profit at the same time.”

He added that he understands the importance of community building and believes that, “If you help people get what they want, you’ll get what you want.”

Hubbard purchased both common and preferred stock shares of the Ronan Cooperative Brewery.

Fellow owners and steering committee members Gail and Barb Nelson said they look forward to the brewery benefitting both its members and the community as a whole.

They signed on to the project because they want to see Ronan’s Main Street revitalized.

The couple remembers a different Ronan, one with a thriving Main Street in the 70s that was home to clothing, hardware, furniture and drug stores.

“My vision for the role of the brewery is to be a destination point,” Barb said. She added that she’d like to see the return of businesses to Main Street, including another restaurant that is open later hours.

She anticipates the brewery will be a gathering place for many community groups with a welcoming atmosphere for all, including families.

“There’s so much potential,” she said. “It excites me that other people see that as well.”

The Montana Gap

Editor’s Note

Look at statewide numbers and Montana’s economy seems to be doing well. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of jobs in the state of Montana grew 20 percent, according to a report released last year by Headwaters Economics. Personal income grew, as did statewide employment.

But if you live outside a city, though, there’s a good chance you won’t see much evidence of that growth. Just five counties — Gallatin, Lewis and Clark, Flathead, Missoula, and Yellowstone — account for three-quarters of it. In much of rural Montana, residents are slipping away — especially the children and families towns need to keep their schools open. Traditional economies — logging, agriculture, mining — are in decline or require fewer and fewer people to get the work done. For much of Montana, as for much of the rural West, the boom going on in cities like Missoula and Bozeman feels more like a bust. For small towns on their outskirts, that boom next door has brought real problems, from infrastructure to zoning and taxes.

So, last year, a group of local journalists from western Montana, as well as High Country News and the Solutions Journalism Network, got together to ask the question: What are Montana communities, especially rural ones, doing to respond to this trend, to help their residents weather the economic winter? And what could they learn from other communities?

The result is a series of stories, publishing over the next several weeks, that examines how places like Choteau, Seeley Lake and Ronan, as well as Frenchtown outside Missoula and Manhattan outside Bozeman, are grappling with their uncertain future. The answers they’re finding are imperfect. But some common threads emerge: Recreation, beer and a focus on community. Towns like Seeley Lake and Columbia Falls are finding ways to capitalize on people’s interest in walking, biking and four-wheeling on the public lands they once logged and mined. In Ronan, a community-run brewery may help fortify Main Street. And Cut Bank is finding ways to build on the strong sense of community to bring in workers from as far away as the Philippines.

A lot of it comes down to “knowing the formula,” as Choteau’s Blair Patton observed. In the wake of profound economic change, rural communities have to figure out a new logic for survival: What assets do they have that other places don’t? (Mountains are good – but, surprisingly, slag might work, too.) What are their people especially good at? What’s important to preserve, and what can be compromised? Understanding and agreeing on the answers is the first step toward building for an uncertain future.

I hope you’ll read along as we explore these responses and more.

Kate Schimel

Deputy editor-digital

High Country News