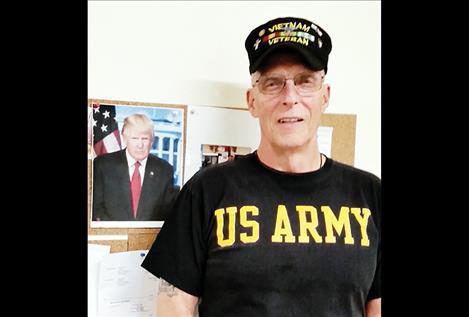

Veteran Spotlight

Jim Mathias September 13, 1951 U.S. Army - Viet Nam C Company 2/22 Mechanized Infantry, 25th Infantry Division A Company 2/327 Infantry “No Slack” E Company 4/503 Airborne Infantry, 173rd Airborne Brigade

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

Jim Mathias was driving a truck after high school but decided he couldn’t keep doing that. He had always wanted to be in the Army and to jump out of airplanes. His mother discouraged his enlistment, but it wasn’t her decision to make, and he enlisted in the Army in December of 1969. His recruiter actually got him to the bus station, and he left for Fort Ord, California for both basic training and AIT (Advanced Individual Training) for infantry. He knew he might have to go to Viet Nam, but it didn’t make any difference to him where he was sent.

From Fort Ord, Jim went to jump school at Fort Benning, Georgia. In August, along with 15 classmates, he flew World Airways from McChord AFB, Washington, to Anchorage, Alaska and on into Cam Ranh Bay, Viet Nam. This was the main incoming center for US troops in Viet Nam.

Jim was assigned to C “Charlie” Company 2/22 Mechanized Infantry, 25th Infantry Division, where the main duties were providing security for “Roam Plows,” which were used to clear huge sections of jungle for roads and shooting the enemy. He was only there three weeks when he was “blown up” and suffered an injury to his vertebra, hip and ankle and also had shrapnel in his face. He made sure the men were medivacked by chopper while he was taken to the hospital in Chu Chi. Jim says your life flashes before your eyes, but when you’re 18, you don’t have a very long story to flash.

After 10 days on crutches, he went back to the field with the 25th. Jim says, “For a week-and-a-half, there was mortar shelling every night with the enemy so close you could hear the tubes, and they threw satchel bombs over the berms, but we never found them.”

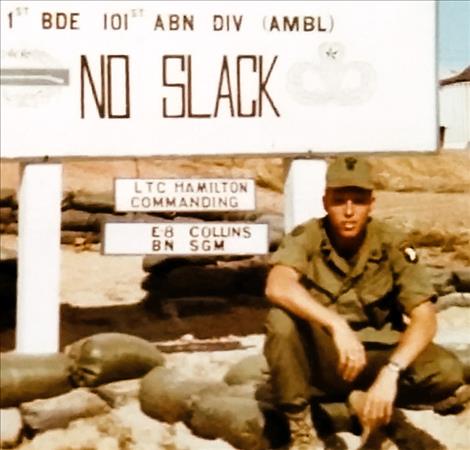

When the 25th went home to Hawaii, Jim transferred to the 101st Co. A 2/327 Infantry “No Slack.” His second lieutenant wanted to “win hearts and minds” instead of taking a strong military stand, and it killed him. Jim filled in for a time but went back to being an E-5 sergeant when a replacement officer arrived. For a three-week period, Jim was the driver for a colonel during the Lam Son 719 campaign near the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone). The colonel ended up getting them two miles over the border inside Laos. Jim was fired for not being enough of a servant. He was glad to get back to the field.

Shortly after the transfer to the 101st, Jim went through a bout of malaria and then transferred again to E Company 4/503 Airborne Infantry, 173rd Airborne Brigade, and began his second tour in Viet Nam. He served three weeks, and then the battalion was sent back to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, through Seattle, Washington. When the plane landed in Seattle, people ridiculed the soldiers and called them “baby killers.” People didn’t understand (or didn’t want to understand) what was going on. Jim took his leave time, but it was hard to go home and leave the military behind. After three days, he was ready to go back to the fort.

Jim spent 1973-76 in Italy and completed two tours in Germany, 1981-84 and 1989-92. His duties in Germany included working with a NATO (National Atlantic Treaty Organization) operation and airspace management at the Fifth Corps headquarters.

Jim retired from Fort Lewis, Washington. Again, it was hard to leave the military behind. After serving 22 years, six months and nine days, he signed out on June 30, 1992, at 1 p.m., just fives minutes from the clocked time he enlisted.

By the Viet Nam era, he thought the military had gotten to be too political. We needed to get back to “yes” is “yes,” and “no” is “no.” Sometimes, Jim felt like the main character in “Heartbreak Ridge.” Orders were to not load their weapons, but Jim told his men to load anyway. One time, they could see a bamboo bush shaking and a Viet Cong soldier jumped out and was shot. If the guns had not been loaded, the specialist walking point would be dead. Jim says combat is not like a video game: you only have one life and you want to save it. It’s not “hatred;” it’s “survival.” Still, it works on you, he said. To this day, he has bad dreams that come and go. Once when Jim was in Missoula, Montana, a plane buzzed Reserve Street and he just froze. Another time, he had to stop doing dozer work because the noise took him back to Viet Nam.

Jim held many positions and jobs during his military career. Jim says anybody can be a boss but it takes more to be a manager/leader. It’s about attitude. Pay attention to detail and focus on others’ “needs,” not their “wants.” Many people today are greedy, he said. As a drill sergeant, he instilled the attitude that no matter what your job in combat is push-will-come-to-shove and you will have to shoot to protect each other. You put everything else out of your mind in combat. Members of the military form a brotherhood no matter which branch of the service they are in.

When Jim interviewed for a top-secret clearance position, the interviewer described him as “colorful.” For a long time, Jim fell from his beliefs and did a lot of drinking. It probably kept him from promotions, but he takes responsibility for his actions. He says, “I did what I did.” Overall, he thinks the military was the best thing to happen to him, the bad and the good. Jim suffered many injuries but continued to do what needed doing. “That’s dedication and commitment. If someone cannot do that, they should stay home.” Even today, he would go back if necessary.

Jim believes strongly in the military and in the NCO corps (non-commissioned officer). He is still in contact with some of his “brothers,” and they talk about what happened and what they did back then.

When Jim was an instructor at West Point, he instilled a sense of “duty, honor, country” in his men. He has a Commendation for Valor, a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart; but in spite of the “ribbons and stuff,” he does not see himself as a hero. With a lot of emotion, Jim says, “It’s an honor to serve my country. People should not thank me. I thank them for allowing me to serve and keep our freedom.”

We do thank you for your service, Jim.