Vanderburg Camp keeps old ways alive

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

2 of 3 free articles.

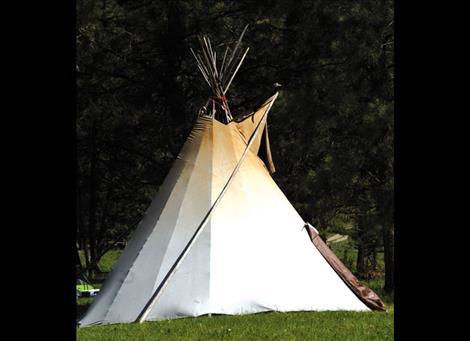

With the sun shining on tipis, campers and tents scattered around the edges of the meadow and Valley Creek winding its way down the drainage, Agnes Vanderburg’s Camp was in full swing the week of June 8-14.

Although Agnes has passed, her legacy lives on in the encampment where Salish Kootenai College students and others come to learn or polish up on Native American skills.

Students need to complete three projects of their own choosing during the weeklong camp, according to Frank Finley, instructor and chairperson for SKC’s fine arts department.

At instructor Dwight Billedeaux’s camp, students learned tool making, shields and painting.

Students Robin Maxkii and Ferrol Brown each covered one of their thighs with a large piece of leather for protection, then used a length of deer antler to knapp arrowheads from obsidian.

The two girls had each already completed a flute, a flute bag, and a flexible cylindrical sack called a sally bag. Now they were working at knapping — chipping obsidian into arrowheads. It’s a tough task.

“I’ve been doing it for 58 years and I’m not that good,” Billedeaux said. “Knapping was a lost art after the 1850s."

That’s when the Plains tribes began using steel, he explained. A hunter could find a steel arrowhead, pull it out of his prey and pound it into shape again. Eventually the tribes got guns.

Billedeaux said it’s always been his hobby. He grew up in Sunburst, 8 miles from the Canadian border and close to a buffalo jump, so close Billedeaux and his brothers would ride their bikes up there.

An old man with a beard was at the buffalo jump, searching for arrowheads, and he told Billedeaux how to make them. The older gent was an archaeologist, which Billedeaux learned when his father took him up to the man’s camp to learn about knapping.

Billedeaux’s tables weren’t far from meandering Valley Creek, which is low this year, the lowest it’s been since 1988, he said. Diffused light filtered through evergreens, backlighting kids who floated sticks in the icy water and scampered across a log bridge.

Billedeaux used clay and ground rocks to make natural paints and taught students who had an interest.

“Chokecherry twigs make a good paintbrush; not willow, they’re hollow,” he said.

Nearby six hide tanners scraped hair from deer hides.

Tanning teacher Junior Green said the winter hides had been frozen until they could be tanned.

“Fresh is best,” Green said. “A hide warm from the deer is easier to scrape — first the meat side, and then the hair side.”

After the hides are scraped they are soaked in water. Green and his students would then wring out hides and start stretching them before they dried.

“With this 80 degree weather, it takes no time at all to dry a hide,” he added.

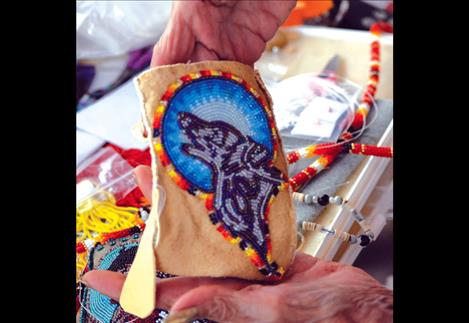

Students tended to retreat to the trees in the afternoon and work on their split cedar root baskets or sally bags with master basket maker Eva Boyd, or bead with master beader Rachel Bowers in their shaded enclaves.

Boyd said three students had completed their baskets. As well as teaching, she was enjoying a visit from her 29th great-granddaughter.

At the beading site, Bowers and Geraldine McDonald had 33 beaders on their sign-up sheet; 10 students were repeaters.

Bowers has been coming to Agnes Vanderburg’s camp since 1969 when she was the cook, first making meals over an open fire, graduating to a propane cook stove and then an old wood burning cook stove that “was the best stove ever,” Bowers said. Someone else brought a MASH tent “and we thought we were in heaven.”

During the 22 years Bowers cooked, the camp was held from April 15 to September 15. But she didn’t just cook; she also taught hide tanning, drum making and beading, and took students looking for medicinal herbs. She decided she liked beading best because she could stay closer to the cook shack and keep an eye on dinner while beading with students.

Bowers, 73, teaches at SKC and has beadwork in the Smithsonian Museum. She still loves coming to culture camp and teaching kids.

Her daughter Judy bought her a tablet and set up Dragon software — a speech recognition software that turn speaking into text — and she is using it to tell her life story.

“I wish every elder could have Dragon,” she said. “The elders have so much knowledge, and we are losing them.”

Student Stormie Perdash was beading a pair of moccasins and a barrette, mostly yellow with sparkles mixed in.

She and her husband Ronnie Harris both started beading two years ago.

Harris had completed three tack and wrap beaded necklaces at the camp, each requiring about an hour and a half to bead.

“Ronnie is really precise when he beads,” Perdash commented.

McDonald agreed that some men are really good beaders.

Flute maker Karolyne Rogers has been coming to the camp for 17 years, driving her motor home named “Ethel,” and pulling her Jeep.

“Ethel is not a cheap date,” Rogers said; she gets about 3.5 miles to the gallon.

Students make plastic flutes to practice on while they craft their cedar flutes, sanding and sanding until the square edges are rounded and drilling the holes.

First year students learn the high register, and second year students add the low register.

Rogers got interested in flute music after hearing R. Carlos Nakai. She was taught by Lakota artist and musician Bob Two Hawks.

“He taught me in his dying process, and he made me promise I would bring flute making back to the Native American culture,” she said.

“I feel like a very honored white woman.”

This year, and several years in the past, Finley has handled general logistics and managed the camp. That means making runs to town for supplies, buying heaps of food before camp began, arranging with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes for firewood and hiring Seth Shield, Cosmo Harlow and Buck Morigeau to set up the tipis.

Although Finley is not teaching this year, he did lead the medicinal and food plant walk and took photos for the American Indian College Fund that granted the camp a large sum of money.

Aggie Incashola was running the kitchen; food was good and plentiful. The camp was clean because Aggie makes everyone pick up things, according to McDonald.

Finley said the camp had 32 students this year and many of them brought their families, plus about eight to 10 people who just came up for the day.

Because the camp isn’t within range of a cell tower, students missed access to their phones but enjoyed talking and telling stories around the campfire and getting to know each other.

“After this camp we are just brother, sisters, mothers, father, grandmas and grandpas,” Bowers said, with McDonald adding, “There are tears the last day."