Governor’s range tour highlights alternative farming techniques

Greener Grazing

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

A few months ago St. Ignatius sheep grower David Sturman walked into a hardware store and was greeted by a neighbor whose salutation was colorful.

“I know you,” the person told Sturman. “You are that radical farmer.”

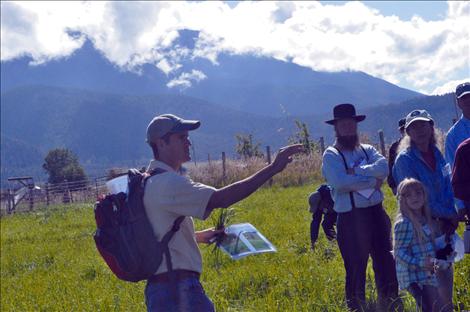

Sturman laughed about the unscrupulous label last week while surrounded by more than 100 inquisitive agriculturalists who traveled from across Montana to learn more about the non-mainstream farming techniques Mission Valley farmers are taking to improve pastureland productivity.

Sturman’s farm was one of three visited as part of the Governor’s Range Tour. The tour is sponsored by the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation.

“It’s an annual event that has been going on for more than 30 years,” said Heidi Krum, rangeland program coordinator for the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. “It is hosted by a conservation district in a different county every year. It is to showcase ranchers and landowners that are doing innovative things and things that are working really well.”

The Lake County Conservation District volunteered to exhibit local farming operations.

“There’s one great thing about Lake County: We are not the largest agricultural county in the state as measured by volume dollars generated, but we are arguably one of the most diverse,” Conservation District Chairman Jim Simpson said. “We have very active forest management programs. We have cherry trees and grape vineyards, potato farms and all the grain crops. We have tremendous diversity and we are doing everything we can to move values for those products higher, regardless of whether it is livestock or crops.”

In recent years the conservation district and staff of the local division of the Montana Natural Resources Conservation Service have worked to help farms test management practices that balk from the traditional methods used in Mission Valley in the past 100 years.

Justin Morris is a pasture specialist for the Missoula office of the Montana Natural Resources Conservation Service who has been teaching ranchers about new management approaches. He likens successful new management practices as the equivalent of the turbo charger that was invented for the diesel engine in the 1990s.

“That turbo charger took the diesel engine and completely transformed its performance,” Morris said.

A turbo charger, he said, operates on the principle that by forcing more air into the engine, the engine can produce more power by producing more oxygen to create more horsepower and more torque.

“Our management on our irrigated pasture is like that turbo charger, and the level of management that we use can totally transform the productive capability of that land and turn it into something much greater than what we are used to seeing it do. But it takes a certain type of management to bring out that productivity.”

The type of management Morris and Lake County Conservationist Ben Montgomery have been helping farmers experiment with is known as high-density grazing.

In this type of grazing, farmers use moveable fence to break their pasture up into small sections called paddocks that hold the entire herd for a few days instead of letting the stock have their pick of acres and acres of open land.

The process can seem more tedious than traditional grazing strategy at first. It takes a half-hour to construct a new paddock of fencing that, while reusable, still has a start-up cost of a couple thousand dollars. Stock tanks also have to be moved with the animals every time a change of paddock occurs.

But Morris and Montgomery see more benefits than hassles for the people that have tried the alternative methods.

Morris said the frequent rotation promotes soil health and encourages stock to eat absolutely everything within the confines of the smaller dinner plate – even traditionally untouched non-native invasive species that aren’t appealing until all the good tasting forage is all gone.

“The animals get more competitive in their grazing behavior and more aggressive,” Morris said. “They not only eat the beneficial plants, but they also start eating the undesirable plants. Here in Lake County white top is one of the big noxious weeds, but we’ve seen through our pasture walks that livestock are utilizing the weeds as a forage resource, and we didn’t have to train them to do that because we modified their environment so they have to be more competitive than each other.”

When the animals eat the noxious plants, farmers spend less time having to spot-spray pesticides to keep the invasive species under control, Morris said. Over time, Morris has seen pastures return to a healthy balance of native grasslands because of high-density grazing.

“That can be a huge savings,” Morris said. “Chemicals aren’t cheap. If you are going to renovate a pasture by spraying it out or tilling it out, those renovation costs are really, really high.”

The forced diversity in diet over a shorter time frame also has significant impacts on animal weight. In an open pasture, animals will put on weight soon after being placed in the field as they chomp away at the best grass. By the end of the rotation, few plants with little nutritional value remain, causing a steady decline in caloric intake and weight. But in a high-density grazing operation, the caloric intake remains steadier, as animals are paced through the pasture’s lush grasses.

“By moving them more frequently and giving them a new fresh bite more often, we can stimulate their appetites so they put on weight a whole lot faster,” Morris said.

Farmers are able to see the increased weight and fewer weeds as they visit the paddocks more often than in larger fields. The frequent close interaction with livestock also increases the chances of spotting subtle signs of animal health problems earlier, Morris said.

“If there is a health issue, I’m going to spot it a lot sooner,” Morris said. “I can basically head off that health issue at the pass, before it progresses 15 or 20 days down the road like I normally would if the animals were out to pasture.”

These side benefits of high-intensity grazing aren’t as glaringly obvious as the blatant differences in paddocked pastureland versus open pastureland seen at David Sturman’s sheep farm. His pastureland is a visual testament to the gains in productivity that he has seen in the past four years.

When Sturman’s family bought the farm, it was clear it would be challenging to stimulate the land in a traditional method. The pasture was rocky and contained little quality grass. The irrigation system had been botched by a backhoe driver gone rogue. Now, a few spots of brown, unproductive land hearken back to what it was like in those days and stand in stark contrast to the thick, knee-high grasses in one of the paddocked fields. Montgomery said that measurements indicate Sturman’s pastures have doubled their productivity since adopting the high-intensity grazing practices, with significant increases expected over the next several years.

Sturman’s herd has grown from six ewes to more than 77 sheep in a four-year time span. His neighbors sometimes eye him cautiously as “a radical,” but it is a system that works for the manpower of Sturman’s farm, which consists of him, his wife, and young daughter. The traditional agriculture industry might not embrace the methods, but the Sturmans do.

“The chemical companies would hate this pasture,” Sturman said. “The only fertilizer we put on it comes from the south end of a sheep.”

Montgomery said he wouldn’t be surprised if some of Sturman’s skeptics eventually end up trying some of his practices because they are so effective.

“Your neighbors might think you are weird,” Montgomery said. “Anytime you do something different they might be looking over the fence asking ‘What’s happening over there?’ A lot of people have done that to David Sturman, but he’s a good sport … I think we’re having a bit of an epiphany in Lake County right now as people look over the fence and decide that they might do some of this stuff. Hopefully they will see that there is something to it.”