Bison roundup conducted as usual after shutdown

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

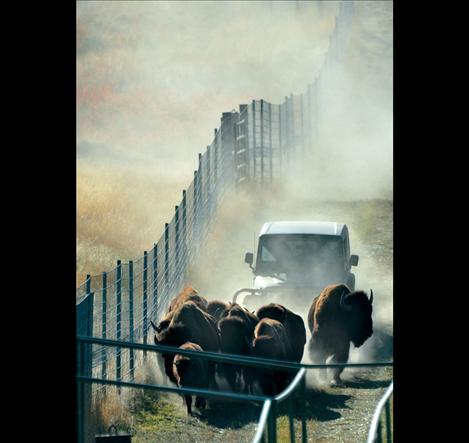

MOIESE – The 16-day federal government shutdown resulted in the closure of the National Bison Range just as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service prepared for its annual bison roundup. Staff were sent home, and the public was alerted that the roundup was canceled, but the bison didn’t get the memo.

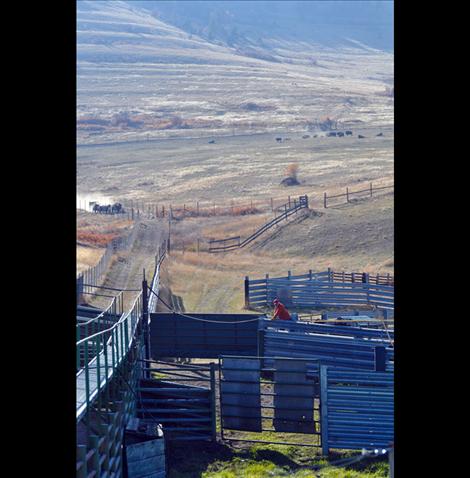

Usually after roundup, range workers move the herd to southern pastures. This year, some of the bison anticipated the annual move and decided to go south on their own, breaking down fences along the way.

“If they run out of forage or water they will go through the fences,” Range outdoor recreation planner Pat Jamieson said. “The inner fences are not as tall and they are electrified, but all it takes is one break to take that electricity down. So often they will go through. A bunch of them did decide to go south, so they weren’t all in one pasture like they typically are, so (workers) had to spend some time gathering those strays up. Some were where they were supposed to be, but some had moved.”

Workers were able to conduct the roundup Oct. 22 and 23, and corralled the herd so 36 of its members could be sold off to maintain a sustainable herd size. Eleven of the animals were also donated to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Blackfeet Nation. The bison destined for the Blackfeet Nation will likely become part of the herd the tribe is building.

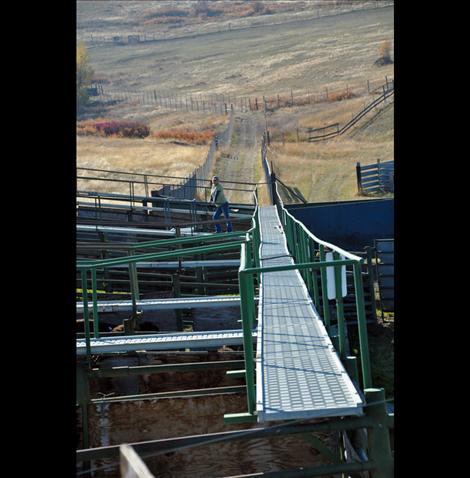

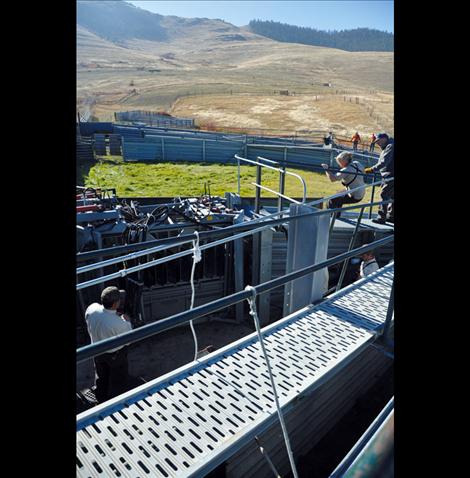

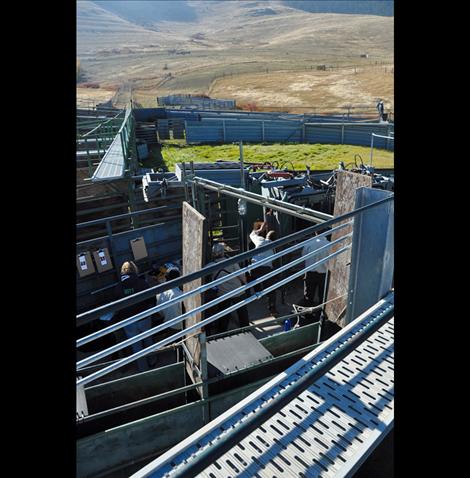

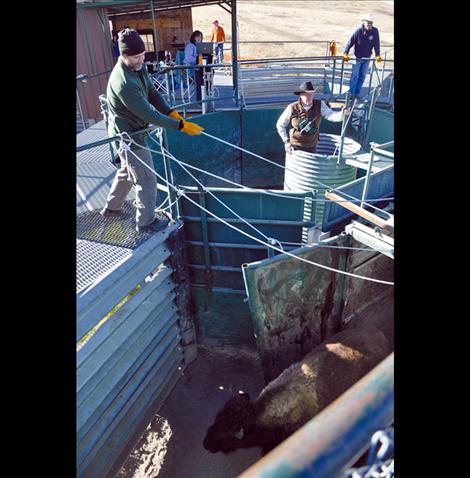

Roundup is an event that has been going on for decades, although modern equipment helps the process. Not too many years ago, the bison were herded down from an upper pasture by riders on horseback, down into the corrals that are made of 10 feet high metal sheeting and filled with a maze of cattle chutes and biological testing stations. Judgment about which bison stayed on the range and which were removed was made arbitrarily by looking at the bison’s physical characteristics.

Today, the bison are herded down by ATVs and Jeeps. They are microchipped instead of branded. The microchip carries records of the bison’s genetics and age. The bison are culled and kept in the herd based on which animals have the most diverse genes.

“This herd is really diverse, considering we’ve been here over 100 years and started with only 36 animals,” Jamieson said. “Private herds saved the bison, because when the Bison Range started in 1908, there were not enough wild bison to populate a place like this,” Jamieson said. “Yellowstone went down to 100 (bison) in the wild and that was the last wild bison, so all the herds have been supplemented and they were supplemented by private bison because that’s what was there.”

The bison used to start the herd at the National Bison Range were brought in from Kalispell, Jamieson said. The Kalispell bison had genetics from the private herd started by Charles Allard and Michael Pablo in the Mission Valley. Other bison came from Texas, New Hampshire, and other public herds that were willing to donate.

This helped increase the genetic diversity of the herd, but biologists have determined that a herd needs approximately 1,000 individuals to keep a healthy gene pool without human intervention. The capacity of the National Bison Range is approximately 350 individuals, which necessitates some degree of human gene management.

“When you have a small population, that’s one way extinction can happen, when you start to lose those special genetics,” Jamieson said.

The National Bison Range works with four other public herds that have populations of less than 1,000 animals and have a “metapopulation” where managers pretend the gene pool is one herd, and work together to swap bison from one range to another range if necessary to reach desired diversity.

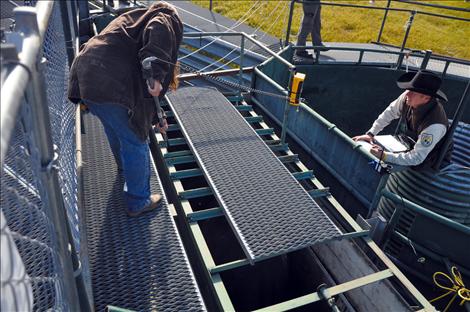

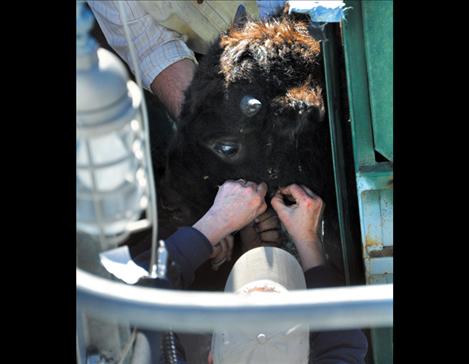

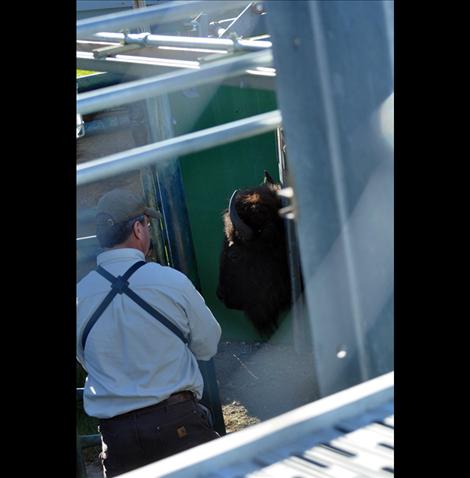

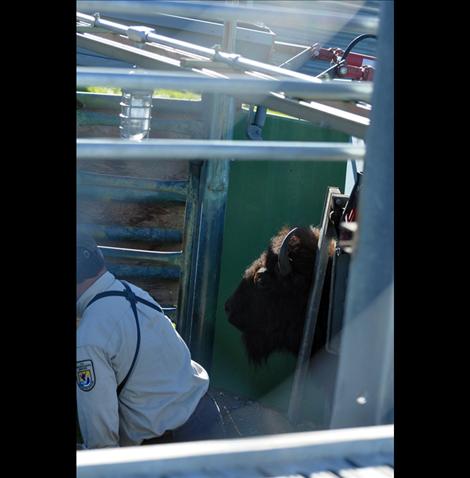

Genetic selection has been made easier by the proliferation of cheaper testing methods. When a bison comes into the chute during roundup, workers take samples of beard hair, tail hair and blood from most of the animals for testing. It’s something that’s happened for a handful of years.

“We started putting the microchips in in 2006,” Jamieson said. “You could do genetic testing a long time ago, but the cost finally went down about that time so it doesn’t break the bank to get it done. We used to do one or two animals for as much as it costs to do the whole herd now.”

Once the bison are microchipped, when they come into the chute in future roundups, workers are able to scan the chip and pull up the bison’s past records and add to them.

“With the microchip, they can say, ‘Oh, it’s you and here’s your little computer page, your face page – like a Facebook page for the bison – and here’s what we’ve got of your history, and here’s your blood work or any health problems,’” Jamieson said.

Animal health officials in Bozeman pick which animals should be culled from the herd and when the microchip is scanned it tells workers on the computer screen if the bison gets to stay in Moiese or move on to another home.

There is an open bidding period in August for the bison. This year 36 bison were sold to five bidders for $48,489.

Some of the bison put up a fight before they move on to their new homes. The pens are scratched and gouged with marks made by animals that were less than thrilled to have their hair cut or blood drawn.

“The ones that really kick and scream are the calves,” Jamieson said. “It’s brand new to them. It’s scary. They are pretty feisty. They are so maneuverable. They can jump pretty high and can almost bend themselves backwards. They are kind of hard to keep into place.”

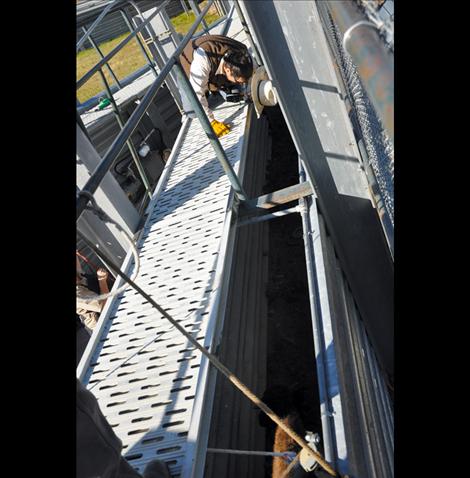

Working with animals that weigh hundreds, if not thousands of pounds, can be dangerous. An ambulance was on the scene to treat any injuries, although staff has never been taken by ambulance to the hospital during the roundup, Jamieson said. Injuries were more common when workers would fall off horses used to drive the bison into the chutes, Jamieson said. Even with safer methods of corralling the bison, there’s still room for error.

“The bison can hit gates and make them go backwards and it could slam into someone,” Jamieson said. “We’ve had bison come out of the squeeze shoots. We had one cow a few years ago, she came out sideways. I’ve never seen people move so fast.”

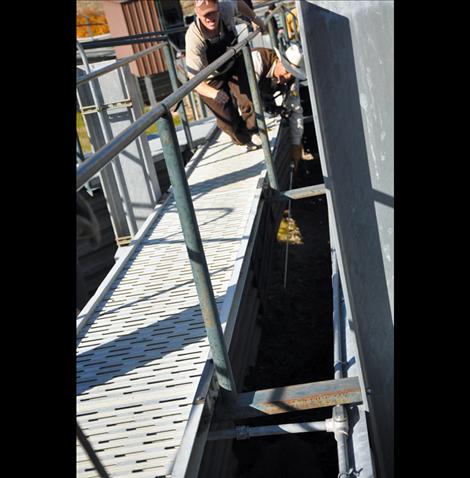

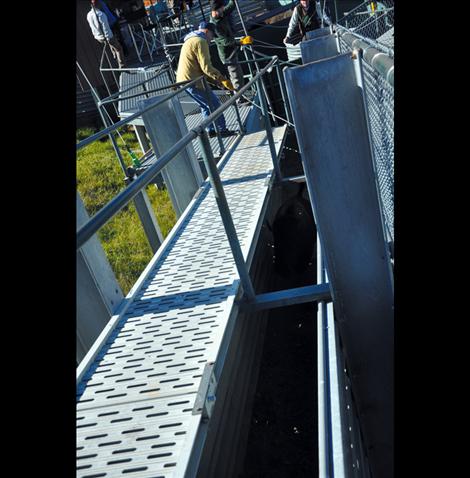

The bison put on a great show for the public and children that often come with schools to see the festivities from a catwalk that gives an aerial view of the roundup. This year, the crowd was thin because the government shutdown shifted the roundup date back so far.

“It is too bad we didn’t have the schools come,” Jamieson said. “They enjoy it. It was quieter for the bison because they don’t have a lot of kids going ‘looky! looky!’ We’ve talked about whether or not we should not have people up there because it might make it less noisy for the bison, but this is an opportunity to let the public see what we do …You get to see what we do with your tax money.”

If the shutdown had lasted longer, roundup likely would have been conducted anyway, because it is absolutely essential to managing the herd, Jamieson said.

“We have to do this,” Jamieson said. “It’s for the safety and health of the bison and protection of the habitat. This is what we are here for. It’s the priority.”