Montana Supreme Court: Oldhorn confession useless

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

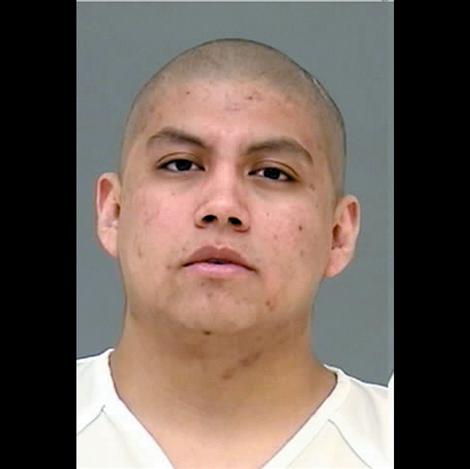

HELENA — The Montana Supreme Court ruled last week that Lake County prosecutors will not be able to use the confession of Clifford Oldhorn if they decide to retry the man for the 2005 homicide of Harold Mitchell that occurred in St. Ignatius.

The unanimous decision, written by Chief Justice Mike McGrath, upheld the January 2013 ruling by Judge C.B. McNeil that released Oldhorn from a 100-year sentence handed down by a jury in August 2011 and ordered a new trial be held in the case.

“The transcript of the interview shows (Lake County Sheriff’s deputies) carefully and deliberately avoided contradicting Oldhorn’s belief that he had been granted immunity by ignoring his questions and affirmatively telling him (the county attorney) had ‘not changed his mind,’” McGrath wrote. “We will not condone the use of deception to obtain a confession.”

The twisted tale of Oldhorn’s confession began in 2007, more than a year after 73-year-old former Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribal Chairman Harold Mitchell was found dead in a burning trailer house on July 7, 2005. The State Crime Lab determined he had been beaten and died of a knife wound to the carotid artery before the blaze started. The case remained cold until two prisoners hatched a plan to break their silence, with a goal to get reduced time for their previous convictions.

According to court documents Oldhorn was 21 years old at the time, halfway through a five-year sentence for burglary, and housed at the Great Falls State Prison. Oldhorn’s cellmate was Robert Gardner, a 29-year-old serving a 50-year sentence for killing a Missoula teenager by shooting the victim in the head and burying the body while the teen was still breathing.

Oldhorn and Gardner developed a close relationship, and one night Oldhorn confessed to Gardner that he had once been a confidential informant and knew some information about a “murder rap.”

Oldhorn offered to relay the information to law enforcement through Gardner, in hope that Gardner’s sentence would be reduced.

The plan didn’t work. Gardner is still incarcerated in the Montana State Prison in Deer Lodge, with all of his 50-year sentence intact. Instead, the confessions brought forth by the pair landed Oldhorn in prison for Mitchell’s death, and the three men he snitched on as perpetrators of the homicide ended up walking free.

The confession trail began like the childhood game “telephone,” when Gardner contacted Great Falls detectives who had worked with Oldhorn in the past. Gardner told the detectives he had friends who knew about the murder of Mitchell. Lake County Sheriff Jay Doyle, who was a detective at the time, asked to meet with Gardner.

Gardner asked for a reduced sentence and immunity for his friends.

Doyle talked with Lake County Attorney Mitch Young, who on Dec. 3, 2007 sent a message to Gardner that read:

“After speaking with Detective Doyle, I would agree not to file charges against your sources for any collateral crimes committed by them in the course of this incident. I will not, however, offer immunity for any acts which would constitute accountability for the homicide of Mr. Mitchell. If either of the sources was involved in the homicide, their cooperation with the police would certainly be viewed favorably in any subsequent proceedings.”

The letter sent to Gardner was sealed in the same envelope as a letter from Doyle that said: “Mitch (Young) did agree to give immunity to your friends.”

More than four months later, on April 2, 2008, Oldhorn wrote a letter to Doyle that identified himself as a witness who was outside of the house at the time of the crime.

“If I testify you already promised me immunity and I still have that in writing but would the prosecutor be willing to suspend the rest of my five year sentence?” Oldhorn asked.

Doyle interviewed Oldhorn in Great Falls on April 18, 2008 with Young, and Lake County Detective Mike Sargeant.

In the middle of reading Oldhorn his Miranda rights, Doyle asked Oldhorn questions about whether he had seen the letters sent to Gardner. Oldhorn said he had, and the Miranda rights reading continued.

Oldhorn told the investigators he was outside of the house during the homicide’s events, but the story changed after assurances from Sargeant and Doyle.

“One of the things that you have to understand;” Sargeant told Oldhorn, “Even if you ... were in the house doesn’t make you a participant.”

Oldhorn responded.

“So if I seen it happen and I didn’t stop it, then I ain’t got nothing to do with this then, I mean,” Oldhorn asked.

Doyle reassured him.

“If you didn’t actively have any active participation in planning that thing out, you know that’s cool,” Doyle said. “We can work with that.”

Oldhorn went on to admit he was inside the home at the time of the crime. He gave a statement to police that said he and three others went to Harold Mitchell’s home with a premeditated plan to rob the elderly man.

According to Oldhorn’s statements, he couldn’t bear to watch as Mitchell was beaten, and went outside, but could still hear Mitchell’s screams of pain.

The other three men exited, and one was instructed to clean up the scene.

The man took a can of gasoline from the trunk and went back to the home and doused the body in gasoline.

The men left and the St. Ignatius Volunteer Fire Department found Mitchell’s body in the burning home shortly afterward.

The man who allegedly doused the body corroborated Oldhorn’s statements.

Two years after the confession, on April 22, 2010 Young charged Oldhorn with deliberate homicide. Three other men were also charged in the death and were all booked into the Lake County Jail by summer’s end.

Oldhorn was transported to Lake County Jail, where he was told he had been moved for a hearing, but was not told what the hearing was for.

On April 28 Oldhorn met with Doyle and Sargeant. Doyle asked if Oldhorn was surprised he had been transported and in their discussion Oldhorn told the investigators “My main concern was, you know (the second witness) and I came forward because, you know, Mitch Young said that we wouldn’t be, that we would have immunity from all of this.”

Doyle and Sargeant did not immediately respond and continued to question Oldhorn about the homicide. Finally Doyle gave a response to questions of immunity.

“I know that Mitch (Young) has, as far as I know, he’s not changed his mind. I think he talked to you in Great Falls ... Ever since then, it has been the same thing.”

Oldhorn learned after the interview that he had been charged with deliberate homicide.

In December 2010 Oldhorn asked to exclude his statements on grounds they were involuntary and would not have been had he understood that he was not granted immunity. The district court did not hold a hearing for the matter, and rejected the request to exclude the statement based predominantly on the judge’s examination of only the Dec. 3, 2007 note sent to Gardner.

“The ‘immunity’ letter from the Lake County Attorney expressly excluded any acts which would constitute accountability for the homicide,” Judge C.B. McNeil stated. “That is exactly the charge against the Defendant for which he did not receive prosecution immunity.”

The case moved forward, and as proceedings progressed, Oldhorn stopped cooperating with law enforcement, and refused to testify against the three others accused.

In summer 2011, Lake County prosecutors dropped charges against the other suspects, and Oldhorn went on trial. Oldhorn said he had lied about the statements he made to law enforcement. A jury took less than two hours to delivery a guilty verdict.

Oldhorn was sentenced to 100 years and his attorney appealed to the Montana Supreme Court.

On Nov. 12, 2012, the high court sent the case back to Judge McNeil with instructions to conduct an evidentiary hearing about whether or not Oldhorn’s statements should have been excluded because of false promises of immunity. After the hearing Judge McNeil reversed his decision, and ruled that Oldhorn’s statements should not be admissible, and a new trial would have to be held.

After 17 months in prison, Olhorn was released, only to be arrested two days later for probation violation and sent back to prison for preexisting deceptive practices, burglary and theft convictions. He remains in the state prison in Deer Lodge. His 15-year sentence for those crimes was reduced May 9 by the Montana Supreme Court Sentencing Review Commission that found the punishment to be excessive and lessened it to a 15-year term, with 10 years suspended.

State Attorney General Tim Fox appealed Judge McNeil’s decision to grant a new trial and suppress Oldhorn’s statements.

The letter from Young to Gardner was clearly conditional upon Oldhorn’s level of involvement with the murder, Fox wrote in his appeal brief. Furthermore, Oldhorn’s testimony in the evidentiary hearing to dismiss the confession should not be taken as truth, Fox wrote.

“Nothing about Oldhorn’s evidentiary hearing observations about his beliefs regarding the immunity offer and subsequent confessions hold water,” Fox wrote. “This is because of the multiple contradictions in Oldhorn’s own confessions, coupled with his prior testimony at trial in which he admitted lying in the context of this case, and, most importantly, because of his 1/4/13 testimony that he fabricated an enormous lie in an attempt to engineer a benefit.”

McGrath and four other Supreme Court Justices did not agree.

The terms of Young’s letter to Gardner were “not readily apparent even to those trained in the law,” much less to Oldhorn, who had an eighth grade education, the ruling reads.

“It is reasonable that Oldhorn would instead have relied on the explanation given in Doyle’s letter, which stated simply, ‘Mitch (Young) did agree to give immunity to your friends.”

The justices also decided that they “were also concerned by the manner in which Doyle administered the Miranda warning at the beginning of the 2008 interview.”

“This warning must be meaningful, rather than ‘mere lip service,’” McGrath wrote. “... The Miranda warning given by Doyle was interwoven with explanations and assurances about the immunity offer. Oldhorn testified that Doyle’s reading of the Miranda warning made him feel that everything was all right, and the waiver was simply a formality. Doyle emphasized the immunity offer in a way that downplayed Oldhorn’s rights to remain silent and to be represented by counsel.”

This meant Oldhorn’s statements were not voluntary, the court ruled.

The Lake County Attorney’s Office did not return calls for comment on what future direction the case might take.