SKC students, professor collaborate on research in Maine

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

PABLO — Micmac tribal members traditionally eat fish and moose meat. A meal of moose liver is toxic, due to cadmium in the wild meat. The State of Maine has recommended women and children eat only one freshwater fish meal of trout or salmon per month, due to mercury contamination.

As a pilot project Salish Kootenai College students Trey Saddler, Was’tewin Smiley and Amy Stiffarm, under the direction of Doug Stevens, Professor at SKC, traveled to Maine and did research on mercury levels in the food supply.

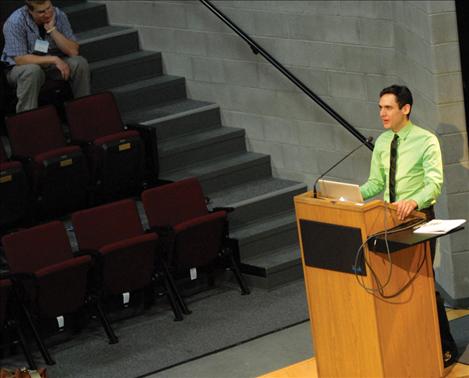

On June 24, Saddler, a junior at SKC, presented information from their research at the Tribal Environmental Health Summit held at the Johnny Arlee/Vic Charlo Theater on SKC campus.

Prof. Stevens and his students worked directly with the Aroostook Band of Micmacs, taking hair samples.

A second pilot project took place in Arizona, where students and faculty of Northern Arizona University worked with the Navajo Nation to begin assessing the role of sheep in exposing Navajo people to uranium.

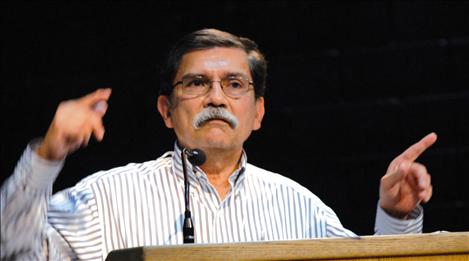

These two pilot projects were part of a larger model Stevens has generated. He wants to form a Native Environmental Health Research network. The Environmental Protection Agency gave Stevens money for both pilot projects. Stevens said tribal communities with environmental issues who have tribal colleges, “have that capacity or resource within the community they can call on to work on these issues.” They also have their own tribal environmental quality departments.

“A lot of tribes don’t have tribal colleges. Where do they go?” Stevens asked.

That’s where the NEHR comes in. It would link tribal people who have a need — anything from samples needing to be analyzed and looking at a contamination site — to “a pool of human resources in students and faculties and physical resources (machines and equipment).”

This would serve a two-fold purpose: give Native American students a chance to do research and “grow” more Native American students who go on to earn masters and doctorates.

Local Native American students might not be Micmac, but they share some cultural similiaries, so it’s easier to work with the tribal community and help individual member take ownership of the research.

“We went in and trained the Micmac on how to take hair samples,” Stevens said, and hair is very important to many tribes. “We could say ‘These students will be doing the analysis and treating the samples respectfully.’”

Some SKC students were able to “work the distance (to Maine),” Stevens said, or others did things electronically.

According to Stevens’ abstract printed in the meeting’s program, the two pilot projects “formed the basis for the establishment of the Center for Expertise/NEHR Network as an NIH Native American Research Center for Health,”

SKC can serve as a central hub, as a kind of clearing house, according to Stevens.

The EPA wanted Stevens to take his idea to a larger circle, he said. So he did — the Tribal Environment Health Summit — where many people could get a look at the project, “mull it over and refine it.”

Presenters and participants attended the summit from all around the nation — North Carolina, Washington, D.C., Washington, Idaho, Maine, Michigan, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma and Montana.

Sponsored by the SKC Department of Life Sciences, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the National Institute of Environmental Health Services, the summit focused on community engaged research and sharing experiences, according to Stevens, who moderated.the event.

“The sub-theme is building collaborative community networks,” Stevens said.

Since no one tribe or college has enough money, “You pool your resources,” he said. “We’re forming a team, but what does that team look like? We believe it’s a community.”

SKC offers the only four-year molecular-based biological science degree of any tribal college. It has two tracks — cellular biology and environmental health.Undergraduate student research is an integral part of both tracks. Providing trainng for students interested in the research would address the job market deficit.

Following his presentation, Saddler explained that he got interested in research and science through Prof. Stevens. Saddler has applied for an internship with Stevens. With just one more year at SKC before graduating with his bachelor’s degree in Life Science, Saddler is now considering where he might go to graduate school.

“I’ve been working in environmental chemistry and environmental toxicology,” Saddler said. “Now it’s just a matter of picking my niche.”