Will water compact impact cause economy to dry up or stay afloat?

Hey savvy news reader! Thanks for choosing local.

You are now reading

1 of 3 free articles.

The melted droplets flowing from snow-packed peaks have carved a course through western Montana that people have used to build civilization and economies for millennia.

First, native people utilized the fish, mammals, and plants that drank from and lived in the flowing waters to sustain their populations. In the past two centuries, conquering European descendants came, diverted the water and altered the places into valuable irrigated farmland that is a part of a great American agricultural powerhouse that feeds the world.

The road to the status quo has been rife with conflict between a native system that resisted, but was forced to bend to invading ways, and a group of optimistic pioneers that sought success by taking resources and using them in methods that they had never been used for before in this part of the world.

The federal judicial system has decided that both groups of people – the descendants of natives who had their homelands reduced to a fraction of what it once was and the progeny of early pioneers who came westward in the United States government’s quest for manifest destiny – have valid claims to the lands and waters. But sorting out the ownership has been a decades long headache, particularly in regards to water in the West where Native American tribes have federal reserved water rights. In Montana, the state has set up a special water court that has spent decades adjudicating non-tribal claims, and set up the Montana Reserved Water Compact Commission that also spent decades working out settlement agreements for Montana’s 17 federally recognized tribes, so the claims did not have to be adjudicated in court. Sixteen tribal compacts have been signed, and the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes Water Compact is the only one left on the table, with a June 30, 2015 deadline looming for the Tribes to file their claims if a settlement cannot be reached in the 2015 state legislative session.

An economic study of the proposed compact is underway, after being requested by almost one-third of the members of the Montana legislature.

Proponents of the compact say it would avoid years of costly litigation and greatly reduce the risk of non-tribal members inside and outside reservation boundaries receiving less water if the Tribes file their claims in water court. Tribal representatives say rejecting the compact would spell disaster in a tangled and expensive mess of sorting out claims for irrigators, and almost certain doom for agriculture in the valley.

But opponents of the compact also predict economic fallout if the settlement is approved. They worry property values will plummet as irrigators receive less water than they have historically, setting off a chain reaction that will be inescapable to other business in the valley.

Both groups point to the Klamath Basin in Oregon as the model situation they fear and want to avoid. There, property values have fallen precipitously in the past two years as irrigators with junior water rights face shutoffs from the Klamath Tribes and other senior water users.

Against the flow

Trudy Samuelson is an owner/broker of the real estate firm Mission Valley Properties. She’s been in business in St. Ignatius since 1994 and worked previously in nearby Missoula. Samuelson grew up as the daughter of a realtor – an esteemed value for private property rights is in her blood.

Samuelson said that’s why she opposes the proposed compact: it violates principles she holds close to her heart and threatens her business and the economy of Mission Valley.

Samuelson believes the proposed water compact takes water rights of individual landowners without compensating them.

“I am against taking without compensation,” Samuelson said.

The agreement gives ownership of water running through the Flathead Indian Irrigation project to the Tribes and spells out how much irrigation water is available to irrigators with some wiggle room for efficient farmers to prove their case to get more water if a local management board approves it within five years of passage of the compact.

The proposed system is problematic for Samuelson, who believes people should have the chance to bring their paperwork to the Montana Water Court – her personal property came with forms that explicitly state a specific “water right” – and fight for it.

Samuelson also fears the method used to calculate how much irrigation water irrigators will receive under the compact was far off base. Under the proposal, the most irrigators will receive is 1.4 acre feet per year for irrigation, unless they prove they need more.

It is difficult to prove if the water will be too little because so many irrigators haven’t measured their irrigation water, but Samuelson said she knows many farmers and ranchers who measure their water who feel it won’t be enough to keep up with production.

Fellow Mission Valley realtor and business owner Christopher Chavasse said he has paperwork proving the average delivery to irrigators on the project in 1938 was 4.8 acre feet, far more than what will be allocated under the compact.

He agrees with Samuelson that the proposed irrigation delivery in the compact is far less than what occurs currently.

In the best case scenario, farmers will have to change their cropping habits to accommodate for less water, Samuelson said. In the worst case scenario, farmers lose their livelihood.

“That reduction in water certainly means a reduction in productivity and income and land value,” Samuelson said. “Then you extrapolate that and when somebody needs to get a loan, are the lenders going to start looking at this and say ‘Well, your farm used to produce five ton an acre when you were getting more water. Now that you are cut back and are getting one and a half or two tons, we can’t loan you the kind of money we were, based on production.’”

She worries that without enough water to keep the crops alive, agriculture will falter. Samuelson points to a study by the United States Department of Agriculture that averaged rented pastureland values for Mission Valley acreage in 2011, 2012, and 2013. Irrigated pastureland fetched a price of $64 per acre. Non-irrigated pastureland brought less than half that price, at $29.50 per acre.

The Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation has also determined that land value increases $2,000 per acre when an acre foot of water is added to irrigated land, but did not determine how much land value is lost if you decrease irrigation to the property.

In addition to potentially reducing the amount of irrigated water delivery, Samuelson is concerned about the restricted use of non-quota water that would occur under the proposed compact. Historically, farmers could use non-quota waters that flowed through the irrigation canals when the irrigation project wasn’t collecting it. Using the water in the off-season didn’t count against the amount of water the irrigators could receive.

Under the compact, that water will be measured and counted against the irrigator’s quota for the year. Samuelson said she knows one rancher who thinks he will have to reduce his herd of cattle by 75 percent because of the elimination of non-quota water usage.

The rancher could decide to use more groundwater to meet his needs, but the expedited permitting process for stock and domestic well usage is limited under the compact to wells that produce less than 35 gallons per minute, or 2.4 acre feet per year. Samuelson is concerned because that is considerably less than the 10 acre feet per year permitted in the rest of Montana. Though 10 acre feet per year is 10 times what is estimated to be needed to run a large home with a garden, Samuelson worries setting a smaller limit in Mission Valley will set precedent for allowing smaller allowances elsewhere in Montana, and put a burdensome economic ceiling on ranchers in the valley that could create a ripple effect.

“(There is) potential for huge consequences, to not just ranchers and irrigators here, but to anyone who uses water, every one of us,” Samuelson said. “The consequences are huge and these small towns like Charlo, Arlee, Ronan, the backbone of these communities is the farmers. It always has been, and they are big taxpayers. The businesses here rely heavily on that business.”

She believes the Compact will spell “certain doom” for businesses in the area.

A measured approach

Certain economic doom is exactly what representatives of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and other compact proponents say they want to avoid in passing the water compact.

They are the first to admit that the document is far from a utopian situation where everyone got exactly what they wanted and the status quo remained the same — steep sacrifices on both sides had to be made to get the compact to where it is today.

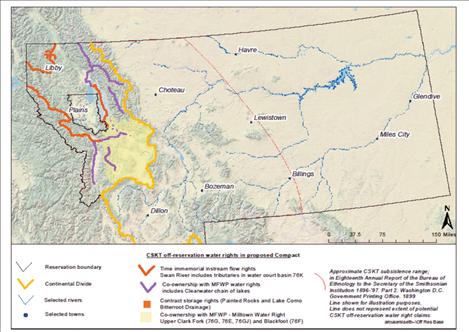

The Tribes claim huge concessions were made on their part in order to get a compact. The Tribes limited their off-reservation water rights claims to eight standalone in-stream flows, and 14 stream rights west of the continental divide that would be co-owned with the state of Montana. This is far less than the estimated 10,000 claims the Tribes seek to file as far east as Billings in the Tribes’ original home territory if the compact doesn’t pass.

Proponents say the potential economic impact of the 10,000 claims being filed is significant. A number of claims that the state and individual property owners have spent millions of dollars on and decades adjudicating would be thrown back into court to fight against a water right with an almost unbeatable time immemorial priority date.

Attorney Hertha Lund is a seasoned water attorney who represents a group of business owners from across the state that call themselves the Concerned Citizens for the CSKT Compact. The businesspeople are concerned not passing the compact will have dire consequences for farming, ranching and other business endeavors outside of Mission Valley if the Tribes file claims.

According to a report released by the Department of Natural Resources Commission in May, it took 8.5 years for the state’s water court to finalize 57,000 claims. Lund estimates it would take 10 to 20 years to handle the additional claims if the compact isn’t passed.

“If we fight there won’t be enough attorneys because there are so many people who have water rights that would be implicated in adjudication,” Lund told legislators at a May hearing.

It will be boon for the lawyering business, and a burden to everyone else, she said.

The attorney’s fees in a water rights battle can be staggering, according to Lund.

A typical claim can have as many as four or five people litigating, and each person’s legal fees can be as much as $5,000 per month. A claim usually takes one year to adjudicate, Lund said.

The high costs come with the complicated nature of water law and Indian law, according to Lund. To have a strong case people who understand — and charge top dollar — the overlapping intricacies of those laws have to be hired. Water measurement has to be done. Sometimes people have to be hired to dig to find documentation that supports historical use, Lund said.

All in all, it is an economic and litigious nightmare that Lund said her clients would like to avoid.

Tribal attorney John Carter sees additional complications that could arise within the reservation boundaries if the Tribes file claims, particularly in regard to water flowing through the Flathead Indian Irrigation Project. The project, one of the largest in the United States, was built in 1908, two years before the reservation was opened to homesteading by non-tribal members in 1910.

The 1,300 miles of canal pull from multiple streams and rivers, and are built so water runs straight through, Carter explained. The system was never anticipated to handle a jumbled mess of junior and senior water rights based on tribal and non-tribal status.

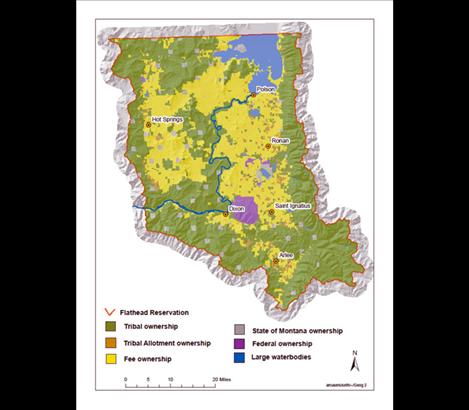

Carter pointed to a map of the problematic checkerboarded land pattern.

“The canals and the ditches run from tribal land, which is green, to federal land, which is purple, to individual Indian land which is orange, to yellow land, which is fee – either Indian or non-Indian owned,” Carter said. “A ditch will run through 15, 20, 30 different ownership patterns as it’s running, and the project was never built to serve by priority date. So if we end up in adjudication and priority dates are upheld under current federal law, then the project gets shut down because it can’t do it. That’s about as simple as it gets. It simply can’t serve by priority date.”

The compact would declare the water running through the irrigation project as a tribal water right with an 1855 priority date. It denies people like Samuelson their day in water court to fight for their claims, but Carter said it was the only solution the Compact Commission could come up with solve the checkerboard problem.

The Tribes, federal government, and state worked diligently to create a management process that was fair, Carter said.

Under the compact, irrigators would have a chance to argue water problems before a unitary management board consisting of two members appointed by the Tribes, two members appointed by the state, a fifth member appointed by the other four members, and a sixth, non-voting ex-officio member appointed by the US Department of the Interior.

If the irrigators were unhappy with the unitary management board’s decisions then the irrigator could appeal to tribal, state district or even federal court.

Much of the compact’s 1,300 page girth is full of abstracts meant to remove the threat of problems that could arise, however. The abstracts contain detailed analysis and predetermination of how much water irrigators will receive – the 1.4 acre feet limit that Samuelson is so skeptical of.

Tribal hydrologist Seth Makepeace admits some irrigators may be allocated less than what they receive currently, but he also points out the some irrigators might receive more water. It’s a double-edged catchfall or benefit that results from averaging the historic water usage in large land blocs.

The system resulted from decades’ worth of historical water measurements studied by the compact creators. But there are a number of mitigation strategies in place to keep farmers from suffering because of lack of water in event the data underestimated what is needed for production, Makepeace said.

Under the agreement there is additional water supply that can be brought to the Flathead Indian Irrigation Project to offset in-stream flow increases, Makepeace said. The state also will help offset pumping costs. Settlement monies would be used to line dilapidating canals and implement other efficiency measures so water is conserved and stretches farther. The compact does eliminate non-quota water that Samuelson worries about, but it is meant to prevent erosion on the project’s canals, Makepeace said.

“We’re mitigating potential adverse effects,” Makepeace said.

The measures were taken to protect irrigators and allow current water use patterns to continue with efficiency improvement, even though the system is already stretched beyond what the project was built to handle, Makepeace said.

All water claims, other than irrigation claims, would be protected from call under the compact, Makepeace said. It would also offer clemency and grandfather in more than 1,700 “outlaw wells” that have been drilled since a 1996 court order instructed the Department of Natural Resources and Conservation to not permit new wells on the reservation, until a final water rights adjudication or settlement was finalized. Approximately 900 of the well owners have filed the claims with the DNRC, and the organization has them filed away, waiting to be processed. Another 800 or so claims have not been filed because the owner chose not to file them. There is a suspected unknown number of secretly drilled and undocumented wells, according to Makepeace.

“Some call them outlaw wells,” Makepeace said. “Right now, their status is in limbo. The water rights compact, as it currently stands, would bring those existing wells in as valid state law based water rights.”

The 2.4 acre-feet limits placed on future domestic or stockwater wells drilled on the reservation – which Samuelson takes issue with – also has a very business oriented reasoning behind it. If the Tribes can limit, track and conserve as much water as possible, it stretches further and provides for future development, tribal attorneys explained.

In most other Montana Tribes’ water compacts basin closure resulted from the settlement, which hinders development.

“(The compact) is a mechanism to allow future development of water rights on the Flathead Reservation, both Tribal and non-tribal and really avoids the issue of closing the Flathead Indian Reservation to new developments of water,” Makepeace said.

It’s an agreement that Polson realtor Ric Smith said is sound and should be implemented. He believes the agreement is fair and will help prevent tearing the community apart.

“Being a good neighbor is good for business,” Smith said.

The potential for social unrest, in addition to economic consequences that could occur if the compact does pass, are things that Tribal Attorney Carter said people should consider.

“If we don’t get a settlement, we’re going to need a whole lot more social and economic services,” Carter said. “It’s going to be a political, economic and social nightmare. Not only on the reservation, but off the reservation.”

The Klamath Calamity

Both Carter and Samuelson use the decaying situation in the Klamath Basin of Oregon as an example of what they don’t want to happen in the Flathead Basin.

Robert Unruh is a farmer who has lived for 40 years in the Klamath Basin. He and his son farm 700 acres of irrigated potatoes, wheat and alfalfa.

Ten years ago almost all of his neighbors were also farmers. Then, in 2001, major water shutoffs were implemented per requirements of the Endangered Species Act to protect fish species in the Klamath River. The valley, with an estimated $600 million in annual agricultural output, was hard hit. The results were so drastic that irrigators, the neighboring Klamath Tribes, environmental groups, and state officials from California and Oregon came together to try to draft a settlement that would be beneficial to everyone.

The Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement gained state legislative approval in 2010, but has languished as it waits for Congressional budget approval.

In 2011, the adjudication process for the Klamath Tribes determined the tribes had time immemorial senior rights to irrigators, and the Tribes called those rights in summer 2013 and 2014 to protect the fishery. Irrigators were left high and dry.

The combination of water curtailments have crashed the economy in the Klamath, with some estimates putting the loss of land value at $500 million in 2013 alone.

“It’s devastating,” Unruh said. “Maybe two out of 10 of my neighbors have farms now. You see little communities drying up and moving away. Almost 50 percent of our workforce has left.”

Part of the hardship came from lack of water, and part came from litigation costs.

“It’s hard enough to grow the crops and get them to sell,” Unruh said. “But to have to pay to fight the government too? You can’t do it.”

Unruh said he is a conservative who can understand why other conservatives might oppose certain elements of the Klamath agreement, like dam removal, but after much study it makes much more sense than litigating to no end.

Klamath Tribal Chairman Don Gentry agrees, and said the Tribes did not want to impose economic hardship on their neighbors.

“We’ve long favored settlement,” Gentry said. “When you go through the process there are winners and losers … You put things in the hands of a judge. It’s costly. It’s risky.”

The Klamath Tribes have been working through the adjudication process for almost 40 years, with average of $1-$2 million annual price tag for legal fees for those efforts alone.

If a settlement is not reached, the Tribes anticipate another 20 years of water-related court battles. It is too much for the community to handle, Gentry said. When the Tribes called the water last year and intense drought set in even the staunchest of critics who had denied the Tribes’ rights to exist came to support passage of the agreement.

“It really rocked people to the table,” Gentry said.

Reaching a consensus for an agreement was far from simple, said alfalfa grower Gary Derry of Malin, Oregon. Thirty-seven different entities participated in the negotiation.

“We wanted to litigate,” Derry said. “We wanted to fight, but we researched and found out it is really expensive, and there really aren’t many winners … If you are going to fight the Tribes you better have deep, deep pockets.”

It was an emotional issue people had to work through. The Klamath Tribes wanted to protect resources it has used for thousands of years, even as stubborn ranchers wanted to fight for opposing interests that had been engrained in their families’ centuries of farm work in the basin.

“The best advice I can give is: Lose track of emotion, folks. It know it is hard when talking about your way of life, but so many times what you hear is emotion, not fact,” Derry said. “There lies the problem in moving forward.”

Derry said people in the Klamath Basin had to make a determination about what they ultimately wanted and were willing to risk. The people on different sides of the issue weren’t necessarily wrong, Derry said. They just realized it wasn’t a fight worth having.

“Regardless of what side of the fence you are on, you owe it to yourself to understand your jeopardy,” Derry said. “It will not be the same. Nothing will ever be the same.”

Derry said had the groups come to an agreement sooner, irrigators might not have had their water shut off the past two years.

Some agreements have been worked out with the Klamath Tribes so the irrigators receive some water, Derry said.

“We don’t have an agreement that is funded yet,” Derry said. “But we have relationships with folks that we never talked with before. That’s improvement.”

Derry intends to keep fighting with his neighbors to have the Klamath agreement passed by Congress.

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribal Attorney John Carter said the Tribes don’t want to go through the ordeal the Klamath Tribes had to in order to get a settlement.

“After the (Klamath) Tribes won in court, the parties sat down and agreed to a deal,” Carter said. “We’ve already got the deal worked out.”

Economic investigation

The University of Montana Bureau of Business and Economic Research will spend the summer months conducting an economic study of the proposed financial impact of passing or not passing the compact.

A team of four or five economists will come the Flathead Basin to conduct the research, bureau director Patrick Barkley said.

“The important thing to note is that neither of those scenarios is the status quo, so it is a very challenging study to work out,” Barkley said.

The researchers will take a look at the overarching economic view “from 30,000 feet above,” Barkley said. The researchers are independent.

“We are not an advocacy organization,” Barkley said. “We have no skin in the game.”

Ronan farmer and State Rep. Dan Salomon told fellow legislators May 13 that the study is meant to address comprehensive concerns into the matter, not just one side of the issue.

“The intent is to ask all parties that have an interest in this to present things and be involved in this,” Salomon said.

Senator Jennifer Fielder of Thompson Falls had one burning question she wants answered: “I think what we really want to know economically is … what is the change to the landowners because of a change in the historic amount of water that they’ve been using to what is now proposed in the compact. That’s the biggest concern I think I’ve heard from the irrigators.”

The report is expected to be released this fall.